Through his pioneering role in the green bans movement, the union leader made environmental concerns mainstream

The environmental and social justice activist Jack Mundey died at the age of 90 in Sydney this week. Unusually for a lifelong radical, he has been remembered by many as a true Australian hero.

Mundey has been widely celebrated for his internationally pioneering role in the green bans movement of the early 1970s. He was secretary of the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) when it imposed 42 union bans on potential construction sites in the state.

These green bans provided a lifeline for scores of NSW resident

action groups and played a crucial role in saving large tracts of Sydney

from demolition to make way for property developments and expressways.

Without these bans, Sydney

would not have retained much of its inner heritage suburbs of The

Rocks, Woolloomooloo, Darlinghurst and Glebe, scores of heritage

buildings in Sydney’s CBD, Kellys Bush Park in Hunters Hill, parts of

Centennial Park and the Botanical Gardens, housing for the Aboriginal

community of Redfern and heritage areas in the regional city of

Newcastle.Mundey has been widely celebrated for his internationally pioneering role in the green bans movement of the early 1970s. He was secretary of the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation (BLF) when it imposed 42 union bans on potential construction sites in the state.

These green bans reflected Mundey’s visionary view that radical movements for social justice should encompass an ecological awareness. For a generation of activists of which I was one, he brought environmental concerns into the heart of urban and mainstream politics. He pushed for notions of democratic urban planning, critiqued dependence on the car and campaigned for public transport.

Mundey’s love of nature and the environment first developed in the forests of northern Queensland where he was born in 1929. His father, a dairy farmer on the Atherton Tablelands, was poor. His mother died when he was six and Jack was brought up by his father and older siblings.

Mundey put himself on the line for countless causes. In May 1965, the anti-Vietnam war movement was protesting against conscripts being sent to war when, in an Australian first, Mundey and two other activists held a sit-in and were arrested.

Throughout the 1960s, Mundey led thousands of militant builders’ labourers in courageous and often dangerous campaigns for better work conditions. Labourers were poorly paid and conditions were very unsafe. On one occasion, BLF militants heaved a flimsy substandard work shed into a large hole on a construction site. Concrete pours were stopped until basic demands were met.

By 1968, Mundey had been elected secretary of the NSW Builders Labourers Federation. During this period, union meetings were translated into seven languages to meet the needs of members, the majority of whom were migrants. For the first time, women were admitted as members and organisers of the union. In later interviews, Mundey was clear that without this fight for the dignity and safety of workers, he and fellow leaders Joe Owens and Bobby Pringle would not have won rank and file support for their green bans.

As the union was growing stronger, the 1960s property boom was accelerating. Developers dreamed up schemes for wall-to-wall skyscrapers across the city, and thought little of evicting residents and bulldozing the historic neighbourhoods they loved. On the north shore, developers eyed off parcels of surviving bushland for new housing estates. Residents’ action groups sprang up across the city.

The significance of Mundey’s contribution is not just that he was an intelligent and courageous leader, but that he inspired thousands of working-class and middle-class residents to stand with the union. When Mundey was arrested and carried by police out of a building in The Rocks that was threatened with demolition, scores of people, including women in their 60s from Woolloomooloo and The Rocks who had never been arrested before, were carried out after him into waiting police vans. The protest stopped the demolition. I was one of a small contingent from Victoria Street, Kings Cross who were arrested on that day.

my dad has a signed copy of this framed in his kitchen from Jack Mundey. i love seeing it whenever I visit home. its a reminder that working class militancy can be devoted to big ideas, compassion and the environment. what a champion. Vale comrade.

Although the conservative media vilified Mundey and the BLF, he won over many journalists with his capacity to articulate his ideas concisely and calmly. Mundey strongly believed unions had an obligation to act with a socially responsible purpose that extended beyond wages and conditions. The nub of the green bans argument was that communities should have the right to shape and protect their environment, and that the workers whose labour was used to create the built environment should have a say in what was built. Coming from working class communities themselves, Mundey and other BLF organisers understood the desire of communities to defend their right to secure affordable housing.

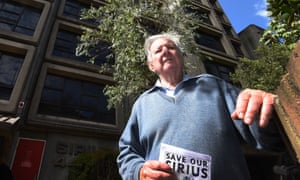

In 1995, he was appointed chair of the NSW Historic Houses Trust. He actively campaigned to save many heritage sites including the Finger Wharf, the Female Factory at Parramatta and the Sirius building in The Rocks.

In 2015, in support of NSW Greens’ Jenny Leong’s successful campaign for the state seat of Newtown, he wrote a letter to the electorate stating that he believed his legacy was under threat: “Neither the previous Labor government nor the current Liberal government in NSW have taken the necessary steps to transition to renewable energy in response to dangerous climate change. Our community should not just be a place for millionaires and motorways. When I was the secretary of the Builders Labourers Federation, our union took the view that our work should improve the lives of the people of NSW, not harm communities or degrade the environment.”

No comments:

Post a Comment