Government’s chief marine scientist says he fears people will lose

hope for the future of the reef, but it is a clear signal for action

The government’s top Great Barrier Reef

scientist says a third mass bleaching event in five years is a clear

signal the marine wonder is “calling for urgent help” on climate change.

One quarter of the Great Barrier Reef suffered severe bleaching this summer in the most widespread outbreak ever witnessed, according to analysis of aerial surveys of more than 1,000 individual reefs released on Tuesday.

Dr David Wachenfeld, chief scientist at the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, told Guardian Australia: “My greatest fear is that people will lose hope for the reef. Without hope there’s no action.

“People need to see these [bleaching] events not as depressing bits of news that adds to other depressing bits of news. They are clear signals the Great Barrier Reef is calling for urgent help and for us to do everything we can.”

Prof Terry Hughes, director of the Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University, surveyed 1,036 reefs from a plane over nine days in late March. The marine park authority also had an observer on the flights.

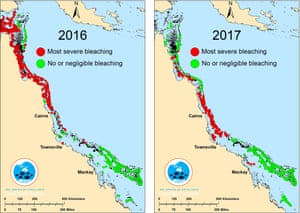

Hughes has released maps showing severe levels of bleaching occurred in 2020 in all three sections of the reef – northern, central and southern – the first time this has happened since mass bleaching was first seen in 1998.

One quarter of the Great Barrier Reef suffered severe bleaching this summer in the most widespread outbreak ever witnessed, according to analysis of aerial surveys of more than 1,000 individual reefs released on Tuesday.

Dr David Wachenfeld, chief scientist at the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, told Guardian Australia: “My greatest fear is that people will lose hope for the reef. Without hope there’s no action.

“People need to see these [bleaching] events not as depressing bits of news that adds to other depressing bits of news. They are clear signals the Great Barrier Reef is calling for urgent help and for us to do everything we can.”

Prof Terry Hughes, director of the Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University, surveyed 1,036 reefs from a plane over nine days in late March. The marine park authority also had an observer on the flights.

Hughes has released maps showing severe levels of bleaching occurred in 2020 in all three sections of the reef – northern, central and southern – the first time this has happened since mass bleaching was first seen in 1998.

The Great Barrier Reef has experienced five mass bleaching events – 1998, 2002, 2016, 2017 and 2020 – all caused by rising ocean temperatures driven by global heating.

Hughes said there probably would not be the same level of coral death in the north and central regions in 2020 as in previous years, but this was partly because previous bleaching outbreaks had killed off the less heat-tolerant species.

The 2020 bleaching was second only to 2016 for severity, Hughes said.

Corals can recover from mild bleaching, but scientists say those corals are more susceptible to disease. Severe bleaching can kill corals.

Hughes said severe mass bleaching had never before hit the southern section of the reef – from Mackay south. That area had high numbers of heat-sensitive corals that “light up like a Christmas tree” when viewed from the air.

“It’s not too late to turn this around with rapid action on emissions,” he said. “But business-as-usual emissions will make the the Great Barrier Reef a pretty miserable place compared to today.”

In February the reef was subjected to its hottest sea surface temperatures since records began in 1900.

Some scientists fear that rising levels of heat being taken up by the ocean have pushed tropical reefs to a tipping point at which many locations bleach almost annually.

Wachenfeld said the reef’s sheer size – it comprises about 3,000 individual reefs – made it resilient, “but climate change brings a new scale of impact unlike anything we have seen before”.

He told Guardian Australia: “Three mass bleaching events in five years is showing us the enormous scale at which climate change can operate.

“No one climate event will kill the Great Barrier Reef, but each successive event creates more damage. Its resilience is not limitless and we need the strongest possible action on climate change.”

The globe has already warmed by about 1C above pre-industrial levels, caused primarily by rising levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere from burning fossil fuels.

Wachenfeld said: “We’re at about 1C and we have just had three marine heatwaves in five years that have all damaged the reef.”

Measures to improve the resilience of the reef include improving water quality, controlling outbreaks of coral-eating starfish, and research and development to improve the heat tolerance of corals.

“None of that is a substitute for strong action on emissions,” Wachenfeld said. “Dealing with the climate problem is the underpinning for everything else to work.”

Under the Paris climate agreement, countries agreed to deliver country-wide plans that would keep global heating well below 2C, with an aim to keep temperatures to 1.5C.

“That’s the window we have to aim for,” Wachenfeld said.

“As we approach and go beyond 2C, I don’t see the tools we have today, and the tools that research and development is working on, will protect the reef.

“The world is heading for 3C of warming – we will not be able to protect coral reefs under those circumstances.

“The reef is, after this event, a more damaged ecosystem, but it can still recover. It needs more help from us and it needs it urgently. This is a call to action.”

In a statement to Guardian Australia, the environment minister, Sussan Ley, said: “It is deeply concerning the reef has suffered another bleaching event and our focus has to be on the ways that we can reduce the pressure on the reef and strengthen its resilience.

“The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority has been monitoring the situation closely and highlighting the concerns over temperatures.

“Thankfully, some of the most recognised tourism areas have been less impacted but that does not change the importance of the issue and the importance of coordinated global action on emissions reduction to reduce ocean temperatures.”

Queensland’s minister for environment and the Great Barrier Reef, Leeanne Enoch, said climate change, pollution from run-off and other threats “are testing the reef’s ability to recover from major disturbances like mass bleaching events, severe tropical cyclones and crown-of-thorns starfish.”

She said the Palaszczuk government had “committed to a zero net emissions target by 2050” and allocated more than $427m for reef protection and resilience between 2015 and 2022.

“The missing piece continues to be leadership and action from the federal government on climate change,” she said.

No comments:

Post a Comment