Extract from Eureka Street

- Andrew Hamilton

- 27 August 2020

When watching a news clip recently I was taken by a young woman’s attitude to the coronavirus restrictions. When asked how they had affected her, she said simply, ‘It is what it is’. The answer suggested an impressive acceptance far from the outrage, frustration and resentment that in the circumstances would not have been surprising. It seemed to suggest humility in the face of a situation that could not be changed.

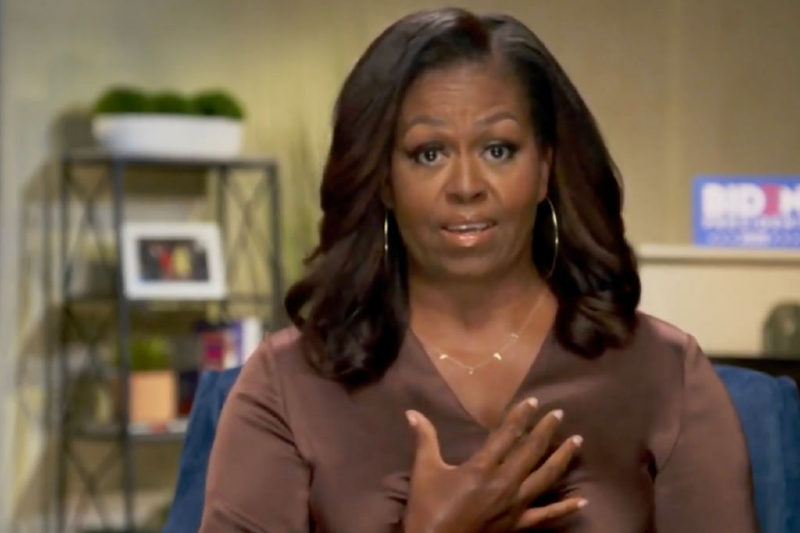

That was the first time I had noticed the phrase, but once alerted I found it everywhere. It was even a killer line in the lead-up to the United States elections. President Trump used it when questioned about the high number of people who had died of coronavirus in the nation. Michelle Obama used it to refer to what she considered Trump’s misgovernment. Some people who commented on the phrase criticised it for being fatalistic; others, like myself, were attracted to it because it was realistic. At all events, it merits passing reflection.

The phrase itself has a relatively short documented history, with different shades of meaning depending on the context. Those who seek a wider cultural reference will think of the Spanish proverb, Que será, será — whatever will be will be. The change of tense from present to future perhaps suggests more space for change. The theologically minded might be reminded of the similar variations of tense in translations of the answer given by God in the Book of Exodus when asked his name. They offer a choice between ‘I am who I am’ and ‘I will be who I will be’.

Whatever of that, the phrase remains with us. What are we to make of it in the time of coronavirus and its restrictions? At least, it must be said, it is better than its contraries. If we were to say, for example, that the coronavirus is what it isn’t, we would be drawn into the maelstrom of social media. It would open the way for such theories as that it portends an extraterrestrial invasion, that it is a plot by the CIA or the KGB to destroy freedom, or that it is a mass illusion.

Another variant of the phrase would be to say that it isn’t what it is. This usage is common among opinionated columnists and lobbyists who argue that that the virus is not a serious threat to health, that business can continue undisturbed by it, and that if given free reign it will die out of its own accord. This represents the triumph of prejudice and self-interest over reality. Compared to these variants, ‘it is what it is’ at least offers us rock to build on.

The desire to build, however, is not necessarily the starting point of all those who use the words. Sometimes people do so to disown responsibility for actions that have done harm, such as injuring someone through careless driving. Like the equally responsibility-deflecting ‘stuff happens’, it can distance people from taking responsibility and allow them to see themselves as untainted actors in a perilous world.

'Michelle Obama’s example suggests that we should pause our judgment of "it is what it is" until we have heard the line that follows it.'

President Trump’s use of the phrase to describe the enormous death toll in the United States was deflecting in this way. As President he had responsibility for leading a concerted response to the virus. The high death toll and his haphazard efforts to minimise the harm of the virus raised serious questions whether his failure to exercise responsibility had contributed to the number of deaths. To those questions ‘It is what it is’ was not a serious answer. The fault, however, lay not in the phrase but in the purpose that it served.

We can also use ‘it is what it is’ as a cop out for doing nothing to try to change a situation that is unjust. As a response to seeing lines of people waiting to be fed at soup kitchens because they are unemployed and have no money, to shrug and say ‘it is what it is’ is pretty weak. To pester the government for better support for disadvantaged people, to join protest marches, or to offer one’s service or financial support to the soup kitchen would be a better human response. The legitimacy of the phrase depends on its human context.

When Michelle Obama’s used it to describe the priorities, behaviour and motivation of the Trump presidency, she might theoretically have been expressing weary resignation. But in the context of her active support of the Biden campaign, it was no more than a description of perceived fact. There was no possibility of change from within, so it was necessary to press for electoral change.

Michelle Obama’s example suggests that we should pause our judgment of ‘it is what it is’ until we have heard the line that follows it. If that line is ‘so let’s give up and forget it’, the phrase expresses a weary and resentful surrender, apathy or despair in the face of defeat, and a decision to put the situation out of mind. It signals an end to curiosity and commitment, and is coloured by this context. Michelle Obama’s implicit following line ‘so let’s get rid of it’ suggests that ‘it is what it is’ forms part of a much more spirited and active approach.

As a basic response to the coronavirus crisis the young woman’s ‘it is what it is’ seemed appropriate and honest. It expressed acceptance of the reality of a situation for which she had no responsibility and which she can do nothing to change. The virus had changed her life in ways that were beyond her control. Her acceptance of that reality could lead easily into action such as seeking new ways of connecting with people, deepening her inner life and contributing to the community.

Acceptance can prepare the way for an active waiting and searching. It does not need to be a surrender. Accepting the loss of some possibilities, it looks for other possibilities. As so often when dealing with locked-in reality, one of Samuel Beckett’s characters has the appropriate follow-up line, ‘I am still alive then. That may come in useful.’

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street.

No comments:

Post a Comment