Extract from The Guardian

Labor prime minister enjoyed extraordinary popularity and led one of Australia’s most transformative governments

Bob Hawke

was a “common man, an absorber, a listener, and in some mysterious way,

a bit of a mirror of the qualities and demands and inputs which

Australians project upon him”, the journalist Craig McGregor noted in a

profile of Australia’s longest-serving Labor prime minister.

The McGregor profile opens with great verve in 1977, with Hawke ensconced at the Australian Council of Trade Unions, shadowing both Malcolm Fraser as an alternative prime minister, and Bill Hayden for the Labor party leadership. The Hawke of this period “drinks like a fish, swears like a trooper, works like a demon, performs like a playboy, talks like a truckie and acts like a politician”. Hawke, McGregor noted, was the typical Australian but oversized – a relatable quality that connected him to voters and underwrote his extraordinary popularity as a public figure.

Robert James Lee Hawke was born in December 1929 in Bordertown, South Australia, the son of a Congregational minister and a schoolteacher. Blanche d’Alpuget records in her 1982 biography that Hawke’s mother, Edith, who read the Bible daily, would find that hers fell open at Isaiah, chapter 9 verse 6: “For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given; and the government shall be upon his shoulder.”

Hawke’s cabinet colleague Neal Blewett notes in the compendium

Australian Prime Ministers that it was family lore that Bob would one

day become prime minister, and the young man fully subscribed to that

view. “From at least the age of 17, after a brush with death in a motor

bicycle accident, Hawke came to share this sense of destiny.”The McGregor profile opens with great verve in 1977, with Hawke ensconced at the Australian Council of Trade Unions, shadowing both Malcolm Fraser as an alternative prime minister, and Bill Hayden for the Labor party leadership. The Hawke of this period “drinks like a fish, swears like a trooper, works like a demon, performs like a playboy, talks like a truckie and acts like a politician”. Hawke, McGregor noted, was the typical Australian but oversized – a relatable quality that connected him to voters and underwrote his extraordinary popularity as a public figure.

Robert James Lee Hawke was born in December 1929 in Bordertown, South Australia, the son of a Congregational minister and a schoolteacher. Blanche d’Alpuget records in her 1982 biography that Hawke’s mother, Edith, who read the Bible daily, would find that hers fell open at Isaiah, chapter 9 verse 6: “For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given; and the government shall be upon his shoulder.”

The family moved to Western Australia in 1939, and Hawke was educated at the Perth modern school and the University of Western Australia, before attending Oxford as a Rhodes scholar. His girlfriend, Hazel Masterson, went to England with him. John Hurst in his 1979 biography says Hazel joined Hawke in adventuring. “They rattled around the countryside in a battered second-hand van. According to one of Hawke’s friends, a ride in this jalopy could be a hair-raising experience. Hawke had a rip-roaring time: those days at Oxford were among the happiest he could remember.” Blewett notes, however, that Oxford “left little imprint on Hawke either intellectually or culturally”.

Hawke returned to Australia in 1956. He married Masterston the same year; the couple had three children (a fourth died in infancy). He began doctoral studies at the Australian National University but went to Melbourne in 1958, taking up an advocate’s position at the ACTU. Hawke prospered there, taking the presidency in 1970 and serving in that role for a decade.

Hawke’s first attempt to enter parliament, in 1963, was unsuccessful. He prevailed in 1980, elected to the safe Victorian seat of Wills. Hazel said she knew Hawke was serious in pursuing his prime ministerial path when he gave up drinking. The former New South Wales premier Neville Wran said Hawke in this phase developed the “rigours of a Capuchin monk”. On his arrival in Canberra, Hawke entered the shadow ministry in the industrial relations portfolio.

Hawke stalked Hayden relentlessly. Hayden spilled the leadership in July 1982 in an effort to hold his rival at bay. Hayden prevailed on that occasion by five votes, which only served to prolong the instability.

The party leadership was finally resolved in February 1983. The Victorian John Button, then Labor’s Senate leader and a Hayden supporter, convinced the leader to step aside. Fraser called a snap election on 3 February, in an attempt to cut Hawke’s likely ascension off at the pass. But Hayden resigned the party leadership on the same day, noting sardonically that a “drover’s dog” could lead Labor to victory.

The government Hawke led is widely regarded as one of Labor’s most successful and one of Australia’s most transformative, with the prime minister assisted by a rare depth of talent in his cabinet.

Shortly after his election Hawke convened a national economic summit with the objective of creating an enduring social compact between government, business and trade unions. The Hawke government created the accord mechanism – an agreement between Labor and the ACTU aimed at achieving wages restraint. It also floated the dollar, opened Australia to foreign banks and financial institutions, dismantled protectionism by reducing tariffs and pursuing trade liberalisation, privatised government assets and pursued tax reform.

Early in the life of his government, Hawke stopped the Tasmanian government building the Franklin Dam. The government’s social policy legacy is as prolific and as enduring as its economic one. It introduced Medicare, compulsory superannuation, the higher education contribution scheme for university loans, and pursued reforms to pensions and welfare payments.

Blewett says while Hawke’s famous charisma underpinned his electoral success – in November 1984 he enjoyed a personal approval rating of 75% – it was his process orientation that gave the government ballast and depth. “His talent for bureaucracy gave his government cohesion, stability and authority.”

Ministers were on a “light rein”, leaving activists in the cabinet to pursue ambitious policy making. The government’s reformist inclinations and its effective internal processes, coupled with rancorous divisions in the Liberal party, saw Hawke lead Labor to four election victories.

Keating’s leadership ambitions had asserted themselves sufficiently by 1988 to prompt the negotiation of the famous “Kirribilli pact” – a secret agreement witnessed by the prominent businessman Peter Abeles and the ACTU secretary Bill Kelty – under which Hawke promised to hand over the leadership to Keating after the 1990 election.

By 1990, the stresses of public life were closing in for Hawke. The rambunctious prime minister-in-waiting McGregor had first interviewed in 1977 was a transformed figure. The gregarious, charming, explosive, burn-the-candle-at-both-ends breakout star of the union movement was now “thinner, frailer, more controlled, honed down to the pursuit of the one thing that always meant more to him than anything else – success”.

In the service of success, Hawke gave up grog and cigars, “and, even, perhaps women”. “The gruelling personal and political ordeals he has gone through have changed the legendary lair/punter/drinker/player/good mate/extrovert of yesteryear; he’s got sterner, greyer, more lined about the face. He doesn’t smile as much as he used to.”

Hawke repudiated the Kirribilli agreement after Keating delivered an off-the-record address at the National Press Club in December 1990. Keating’s sortie, which has become known as the Placido Domingo speech, was a candid and reflective outing prompted by the death of his friend, the Treasury official Chris Higgins.

Hawke took exception to Keating’s reflections: “Paul’s performance was vainglorious and arrogant, disloyal and contemptuous of everyone on the political stage but himself.” Hawke said the performance “strengthened my belief he was not ready for the leadership” and he reneged on the deal.

The government was by this point damaged by an economic recession and paralysed by the standoff between the two dominant figures of the period.

Keating launched an unsuccessful leadership challenge in June 1991, then made a second, successful attempt in December. Blewett reflects: “Given the vanity of one and the pretensions of the other, and given the extraordinary ambition of both men, what is remarkable is not that the relationship eventually broke down, but that it endured for so long.”

McGregor notes that Hawke was a conservative Labor leader and a “middle classer” of the party that came into being representing working people. “When he was elected prime minister in 1983, he was something of a folk hero; people expected him to be a saviour, a leader of inspiration. What they got was a skilful middle-of-the-road politician whose Messiah role shrunk year after year.”

Blewett says Hawke was the greatest Australian prime minister since Robert Menzies. “A great party manager assisted by astute lieutenants, he brought an historically fractious party through a period of profound change without any serious split. His political weight and skills gave him a mastery over his ministers unchallenged until the final months. His imprimatur, or at least his acquiescence, was necessary for every major act of government.”

The former Liberal prime minister John Howard, who, like Hawke, led his party to four election victories, says Hawke was the greatest prime minister Labor ever produced.

At his final press conference after losing the Labor leadership, Hawke was asked how he wanted to be remembered by the Australian people. “I guess as a bloke who loved his country, and still does, and loves Australians, and who was not essentially changed by high office,” Hawke said.

“I hope they still will think of me as the Bob Hawke that they got to know – the larrikin trade union leader who perhaps had sufficient common sense and intelligence to tone down his larrikinism to some extent and behave in a way that a prime minister should if he’s going to be a proper representative of his people, but who, in the end, is essentially a dinky-di Australian.

“I hope that’s the way they’ll think of me.”

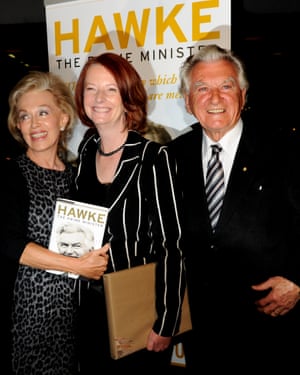

Hawke is survived by his second wife, Blanche d’Alpuget, his children Susan, Stephen and Rosslyn, and stepson Louis.

• Robert James Lee Hawke, Australian prime minister, born 9 December 1929; died 16 May 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment