Whistleblowers who revealed government wrongdoing already face jail.

This week’s raids will only deter others from coming forward

David McBride was almost out of Sydney when his phone lit up.

It was his ex-wife. Something was wrong.

She rarely called when she knew he was behind the wheel.

“She said, ‘I’ve got to tell you something. I’ve got a news alert on my email that said the ABC offices have been raided over the Afghan files’,” McBride says.

“We both kind of nervously laughed, and she said ‘I’ll speak to you later’.”

As McBride continued the long drive home from Sydney to Canberra, federal police were busy sifting through sensitive documents at the ABC’s Sydney headquarters. They had the power to add, copy, delete or alter anything relevant to the 2017 Afghan files exposé on special forces misconduct in the Afghanistan war.

"Taking on the whole government, it sends shockwaves through your life, and not much survives"

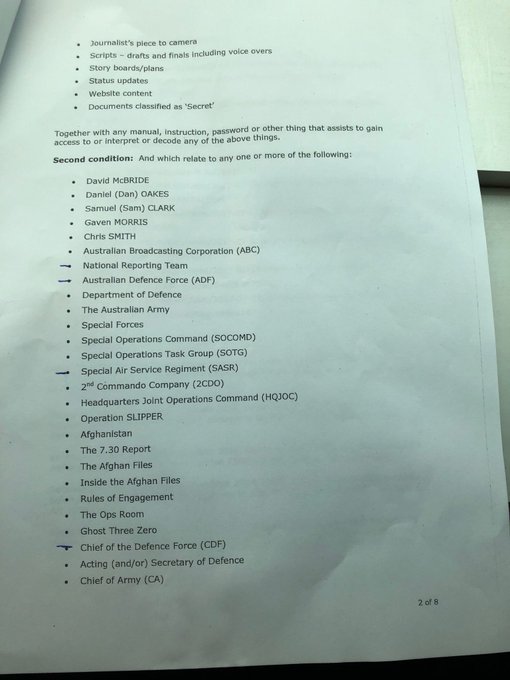

The warrant listed McBride as the police’s first subject of interest.

McBride unleashed powerful forces when he decided to go public years

ago with what he discovered as a military lawyer serving in Afghanistan.It was his ex-wife. Something was wrong.

She rarely called when she knew he was behind the wheel.

“She said, ‘I’ve got to tell you something. I’ve got a news alert on my email that said the ABC offices have been raided over the Afghan files’,” McBride says.

“We both kind of nervously laughed, and she said ‘I’ll speak to you later’.”

As McBride continued the long drive home from Sydney to Canberra, federal police were busy sifting through sensitive documents at the ABC’s Sydney headquarters. They had the power to add, copy, delete or alter anything relevant to the 2017 Afghan files exposé on special forces misconduct in the Afghanistan war.

"Taking on the whole government, it sends shockwaves through your life, and not much survives"

Those forces have already exacted a crippling toll.

“[My ex-wife] would probably say – and I think there’s an element of truth in it – it killed David McBride,” he says. “The man that she married was killed by the defence force, and I’m someone who’s different.

“Doing something like this, taking on the whole government, it sends shockwaves through your life, and not much survives, really.”

The raids have not occurred in isolation. Multiple whistleblowers who revealed government wrongdoing are currently being pursued through the courts with alarming vigour.

The government is prosecuting Witness K and Bernard Collaery, who revealed an unlawful spy operation against Timor-Leste during oil negotiations. Richard Boyle, the tax office worker who revealed the government’s heavy-handed approach to recovering debts, faces a long stint in jail if convicted.

Assoc Prof Joseph Fernandez, a journalism lecturer at Curtin University, has spent years studying source protection and the Australian media. He says the consequences of this week’s raids are clear, regardless of whether journalists are charged.

“Such raids, regardless of what happens here to journalists or to others, will have an immeasurable censoring effect on contact people have with journalists,” Fernandez says.

“In my research in this area over the years, it was clear that even senior public servants are apprehensive about having contact with journalists, even about mundane things, in the wake of laws that enable the authorities to track down sources.”

The McBride matter had been bubbling away for some time before Wednesday’s raid. Guardian Australia understands police have been talking to the ABC since at least September, trying to find a way to access the documents without resorting to a very public raid. The ABC did not hand over the documents. The AFP also maintains there was no notification to the home affairs minister, Peter Dutton, before the raids. He was alerted only after they took place, the AFP says.

But critics have raised suspicions about the proximity of the raids to the federal election and the time that has passed since the original publications.

Prof John Blaxland, a former army officer now with the Australian National University’s Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, says the optics suggest overreach.

“Multiple raids in the one week, so shortly after the election outcome and without a compelling explanation, leave us wondering as to whether this is something that has been pending for some time, something that those authorising them knew would generate controversy that was best left until early in a new term of office, when the political fallout could be contained,” Blaxland says.

“Any inference that suggests our decisions were influenced by anybody outside the organisation is strongly refuted,” Gaughan said.

The police union, for its part, urged the public to remember officers were just doing their job, following the law as it exists. Police were acting on referrals made to them by the defence department.

“I understand that there is intense media reporting in relation to these warrants and I am proud of the way AFP members have professionally executed their duties during this trying time,” the federal police union boss, Angela Smith, told Guardian Australia.

“The members involved are doing their job and doing it professionally.”

Denis Muller, from the University of Melbourne’s Centre for Advancing Journalism, says arguments about the police operating at arm’s length from government miss the point.

Police were acting under old laws when they raided Smethurst and the ABC. The AFP said it was acting under “secrecy offences in Part 6 and 7 of the Crimes Act 1914”. Those laws bar public servants from unauthorised disclosures, and prohibit the publication of official secrets.

In recent years, the powers available to the government have increased dramatically.

In 2015, both major parties helped usher in metadata retention laws, which prompted huge concern for the anonymity of journalists’ sources. Metadata – details about a particular communication, rather than the content of the communication itself – now must be retained by telecommunications companies for two years. A vast number of government agencies are allowed warrantless access to the metadata. Late last year, the Communications Alliance said its members had received requests from at least 80 different government agencies.

Further laws were enacted last year allowing the government to compel technology companies to assist in decrypting private communications. The new powers again threatened a key avenue of communication between whistleblowers and journalists – encrypted messaging applications.

Labor’s Mark Dreyfus has raised concerns about the raids, questioning why they have taken so long, and expressing doubt that government ministers were not aware of the operation. He has suggested a Senate inquiry may be needed.

“The government is responsible for this,” Dreyfus told the ABC. “These are government documents, this is government information, the government referred this to the Australian Federal Police.”

Blaxland believes a “robust examination” of Australia’s intelligence and national security regime is now needed, to take stock of the current laws and to better address serious risks posed by attacks such as the one revealed this week that targeted the Australian National University.

“We know much legislation has been approved concerning these domains in recent times and it is time for a holistic review,” Blaxland says. “Issues that should be addressed range from the industrial-scale hacking of national institutions … the largely unexplained aggregation of powers in the home affairs portfolio and the related discomfort evident within associated security and intelligence agencies.

“I advocate this not out of some conspiratorial obsession, but because I sense the need to clear the air, to assure the public of what is going on and, where practices are suboptimal or excessive, to ensure recommendations are made and enacted upon to see that they are modified.”

The United Nations enshrines the right to access information and protections for sources and whistleblowers through the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Australia has ratified.

Yet a 2015 UN study into source protections, the first of its kind, found governments across the world were failing to ensure “adequate protections to whistleblowers and sources of information”. Clashes between the need for secrecy and the public’s right to know were common, the report found. But where such difficulties emerged, the UN said governments should always avoid enacting laws that restrict free speech.

“When the right and the restriction clash, as they are often purported to do, governments and international organisations should not adopt laws and policies that default in favour of the restrictions,” the UN’s special rapporteur found.

Australia’s whistleblower protections – chiefly available through the Public Interest Disclosure Act – face frequent criticism for their weaknesses. Government whistleblowers must take extreme care to raise concerns internally and with external watchdog agencies before they can go public. Even then, whistleblowers are able to obtain protection for disclosures to the media only in limited circumstances.

It’s a common theme among whistleblowers who have been prosecuted. The ATO whistleblower, Boyle, raised his concerns internally through the PID Act before going public. He now faces a maximum 161-year sentence.

Witness K went to the inspector-general of intelligence and security to raise concerns and seek approval to talk to Collaery, an approved lawyer for the intelligence services.

McBride similarly made internal complaints, sought protection, and went to the police. The leak has already caused him to spend one night in detention, and he faces a long stint in jail if he loses his case.

Despite all the pain it has caused him, McBride says he would take the same course if he had his time again.

“My lifelong friends kind of laugh at the irony of me being a whistleblower, because it’s not what anyone would have expected of me,” he says.

“But when you’re confronted with behaviour which is so bad, you don’t really have a choice, whether you’re a goody two-shoes or not.”

No comments:

Post a Comment