Extract from The Guardian

Most people consuming information online in Australia take no steps to verify its accuracy

• Australians are avoiding the news and think it’s too negative, survey finds

• Australians are avoiding the news and think it’s too negative, survey finds

Given Australia has just been through a federal election cycle where the proliferation of misinformation was part of the voter experience, new research about digital media trends makes for interesting, if sobering, reading.

According to work from the University of Canberra in cooperation with the Reuters Institute and the University of Oxford, a majority of online consumers in Australia, 62%, are concerned about what is real and what is fake on the internet.

This level of local concern is higher than the global average and, the more interested in politics you are, the more you worry about fake news.

Because people are becoming aware that the internet is both a

cornucopia of information, and a platform for misinformation, the new

research suggests a proportion of news consumers in Australia are taking

steps to try and verify what they are reading.According to work from the University of Canberra in cooperation with the Reuters Institute and the University of Oxford, a majority of online consumers in Australia, 62%, are concerned about what is real and what is fake on the internet.

This level of local concern is higher than the global average and, the more interested in politics you are, the more you worry about fake news.

This is good news, obviously. But before we get too excited about this, it’s important to note that this research tells us two other things.

The first is most people consuming information online in Australia take no steps to verify its accuracy. The second is Australians are more likely to share a dubious story without checking it than news consumers in many of the other countries surveyed.

It’s pleasing to see that a proportion of Australian consumers are suspicious enough to check, at least at the level of trying to sift out poor journalism. 36% of the sample reported cross-referencing the reporting of a news event across different outlets to check whether what they are reading is accurate, and 26% say they are seeking out more reliable news sources based on their own research and cross-checking.

Another cheerful piece of news. Digital natives, the younger generations of Australians, are more likely to try and verify online news than older people, reflecting their more sophisticated online literacy, and likely, their lower trust levels in the commodity of news compared with the older cohort.

But back to the troubling side of the ledger. What this snapshot also makes clear is the people currently fact checking are people with higher levels of education, income and engagement with politics.

The people least likely to fact check least are news consumers who don’t know their political orientation – so, in other words, very likely, the undecided voters who determine the outcomes of federal elections.

As the research says: “This group has low interest in politics and news, uses the fewest brands, and accesses them via the fewest channels or sources. They are more likely to be female, younger and have low education and incomes.

“Importantly, in an online political environment tainted by fake news and partisan misinformation, this group also fact checks and verifies stories the least.

“According to this data they are possibly making voting decisions based on the fewest number of sources and are less likely to check them. This reflects a significant population of disengaged news consumers.”

The challenge of knowing what is true in the digital world, a process made more difficult by social media giants who are content hungry but don’t want the responsibilities associated with being publishers, adds to the growing phenomenon of what a couple of American political analysts have described as “duelling fact perceptions” evidenced in contemporary debates about climate change, or whether or not vaccinations are safe.

David Barker and Morgan Marietta say duelling fact perceptions are not being driven by misinformation from politicians and pundits, or from rusted-on partisan points of view, but from the projection of personal values on to facts.

“Values not only shape what people see, but they also structure what people look for in the first place,” the two argue in a book called One Nation, Two Realities.

The Rand Corporation talks about “truth decay” and the threats that poses to evidence-based policy making. It defines “truth decay” as a combination of increasing disagreement about facts and analytical interpretations of facts and data; a blurring of the line between opinion and fact; the increasing relative volume and resulting influence of opinion and personal experience over fact; and declining trust in formerly respected sources of facts.

It is obviously not a new phenomenon that elections are decided by people with light engagement in politics, or that lies get told and promulgated during elections by political actors and associated entities, or that people sometimes cast their votes based on an entirely false premise.

That’s all ever thus.

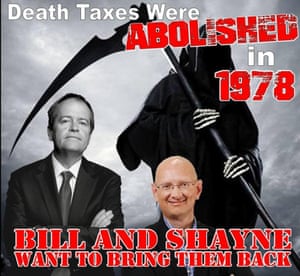

But the digital environment creates challenges that we’ve seen during the 2016 presidential contest in the United States, the Brexit conversation in the United Kingdom, and with the entirely false claims that Labor would introduce a 40% death tax circulated during the recent federal election.

There are no simple solutions to these challenges, but if we allow policy makers to steadfastly ignore a problem which is now clearly before us on the basis that there are no easy answers to it, then our shared outlook is clear.

We are in deep trouble.

No comments:

Post a Comment