Extract from The Guardian

Australia could be a post-carbon superpower – but the energy minister must seize the day

As the gravity of the unfolding climate emergency begins to dawn upon Australians, instead of lies and obfuscation from our elected representatives, we urgently need leadership capable of navigating our economy to a prosperous, zero-emissions future.

Cynically, the prime minister, Scott Morrison, has designated Angus Taylor as the minister for emissions reduction and, unfortunately, telling the truth doesn’t seem to be Taylor’s strong suit. (“You’re wrong, Barry,” interjected Taylor when the former host of ABC Insiders correctly pointed out that emissions were on the rise.)

Taylor never did deliver on his last posting, as the minister for reducing power prices. In his latest derogation of duty, he held back publication of the national emissions accounts. When he did finally front the media he falsely claimed seven times in two and a half minutes that the government’s plans to reduce emissions by 26% to 28% were “laid out to the last tonne” — when the government has no such plan.

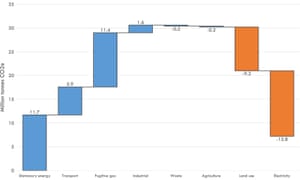

In 2005 Australia’s total carbon emissions were 610 megatonnes. Reducing emissions by 26%, the lower end of our “ambition”, would mean annual emissions of 451 MT. In 2015 our annual emissions reached their lowest point since 2005 at 530.7 MT, some 13% below 2005 levels. They have increased every quarter thereafter. With LNG production set to increase 12.9% in 2019, there is no reversal in sight.

Change in annual Australian emissions 2015-18

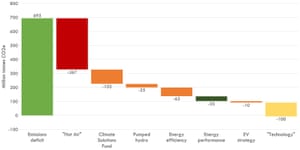

Australia’s carbon deficit and the climate solutions package

The second biggest proposed reduction is the carbon reduction fund, which was set up to buy $200m of carbon offsets annually. In the treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s first budget, he slashed the program to just $47m a year over the forward estimates. Even if funding were restored, the CRF’s total efforts would be swamped by the emissions of just one or two of our 10 operating LNG projects.

The third biggest proposed reduction is the amorphous category named “technology improvements and other sources of abatement”, ie, crossing our fingers and hoping that emissions fall through no efforts of our own.

The CSP even includes 10 MT abatement via an “electric vehicle strategy” – awkward, given Taylor’s derision towards EVs during the election. Regardless, the government has conceded that the strategy won’t be released until mid-2020.

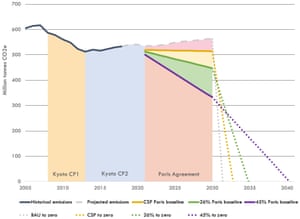

The figure below shows several emissions trajectories. The government’s CSP scenario (the orange line) sees emissions almost flatlining through the Paris agreement period, eventually reaching zero in 2980! Clearly the CSP does not deliver 26% emissions reductions (the green line) by 2030, or deliver Australia’s share of decarbonising the economy.

1.5C emissions pathways for Australia after 2030

For Australia to do our fair share of meeting the Paris budget, the CSP leaves us with the impossible task of decarbonising the economy in just three years from 2030. A steeper trajectory before 2030 gives us breathing room for a more realistic trajectory afterwards.

It’s important to remember why reducing emissions is so important. As Joelle Gergis told RN Breakfast on Tuesday, in terms of climate, Australia is the most vulnerable nation in the developed world. At 2C we effectively lose the Great Barrier Reef, the natural wonder, the biodiversity and the tens of thousands of jobs. We’re on track for 4C of warming, which would make much of the country a living hell.

This month I travelled to China as part of a “Smart Energy” delegation. In Shenzhen, where every bus and taxi is fully electric, we toured the factory of BYD, where many of its 250,000-strong workforce are building the energy storage and transport systems of tomorrow. Our tomorrow, their today.

We toured the highly advanced factory of Jinko Solar. With 10.5 gigawatts of annual production, Jinko is the largest solar panel manufacturer in the world. These “factories of the future” are no longer dependent upon cheap labour, but on big investments, smart manufacturing, world-leading quality systems and highly skilled researchers and engineers. As we dither, China zooms past.

Prof Ross Garnaut paints a picture of Australia as a superpower of the post-carbon world economy. Our world-leading wind and solar resources can and should be harnessed into making the world’s lowest-emissions steel, aluminium and lithium, instead of just exporting ore. Our cheap clean energy can be turned into hydrogen, the “God molecule” of the post-carbon industrial era, and the economics are shifting such that it may soon make sense to export electricity by subsea cable to our south-east Asian neighbours. Has Angus Taylor ever set out a vision for Australia’s energy future that’s even remotely compelling? Anything other than caretaking a highly polluting 20th century energy system while we push civilisation further into climate chaos?

No. Taylor ducks and weaves around the bad news in our quarterly emissions data, suggesting that Australia should be applauded for exporting gas. As experts have pointed out, claims about the environmental benefits of gas are “grossly exaggerated” and “likely to be wrong”, and, if we want praise for small, potential emissions reductions overseas, we must also take responsibility for the large, actual footprint of our coal exports.

Ask Taylor in which year emissions will fall to 451 MT — 26% below 2005 levels — and you’ll get no straight answer.

History won’t be kind to this energy minister for approaching the climate challenge with all the care and subtlety that Captain Smith of the Titanic approached the fatal iceberg.

History will be doubly harsh on Taylor for his failure to navigate a course that captures the economic opportunities of the global energy transition.

• Simon Holmes à Court is senior adviser to the Climate and Energy College at Melbourne University

No comments:

Post a Comment