In 1969, Dennis Hopper and friends set out to make one of the last

great movies of the decade, changing independent film-making forever

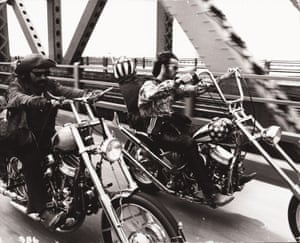

It’s a matter of historical record that Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, and Jack Nicholson

smoked marijuana while shooting in character on the epochal road

picture Easy Rider. They would not be the last to do so, and this writer

would gladly wager that they weren’t the first, but posterity has cast

them as the poster boys for the practice. More so than anyone else’s,

their casual ingesting reflected a devil-may-care attitude that began

with their characters – Captain America in biker leather Wyatt (Fonda),

fringe-jacketed hippie Billy (Hopper) and their lawyer companion George

(Nicholson) – and extended to the men themselves. When they light up, we

catch a glimpse of something real, a roustabout spirit that director

Hopper and his merry band lived as they acted it.

Situated at the end of its decade, Easy Rider literally and

symbolically marks the turning point at which the idealism of the 60s

curdled into the indulgent solipsism of the 70s. Though Wyatt and

Billy’s long hair, sideburns, and far-out couture outwardly align them

with the flower children and estrange them from squares at small-town

diners giving disapproving looks, they’re far from avatars of peace and

love. The tacit prologue, scripted solely in untranslated Spanish

dialogue and the hurricane roar of a jet engine, follows the pair as

they score several bags of high-purity cocaine in Mexico and then sell

it to a client (hey there, Phil Spector!) back in Los Angeles. With a

sealed plastic tube full of rolled-up cash stashed in his motorcycle’s

fuel tank, Wyatt takes off with Billy for New Orleans in time to catch

Mardi Gras. Their quest follows no imperative higher than the desire to

live well and live freely.They’re no heroes, and aside from the part they play in the international narcotics trade, they’re hardly villains. They wish specifically to exist without that dichotomy, to live outside of a close-minded society’s quality judgments about them. Stopping for their first night out, they decide to make camp in the woods instead of using some of their drug money to put themselves up at a motel. They balk at every form of organization, whether it be the humdrum suburbia epitomized by the marching-band parade they infiltrate or the bohemian commune they can’t help but depart. The generous montages depicting the guys astride their hogs, tearing down the highway to the strains of the soundtrack’s many classic-rock cuts, suggest this as their natural state.

Easy Rider blew open the gates for stranger techniques in the mainstream, and long-haired rebels on today’s indie fringes still ape Hopper’s whip-zooms and twitchy back-and-forth cutting. Still, his ramble through the American south stands out not only for its daring ethic, but also for the success with which it was received; Easy Rider earned distributor Columbia a staggering $60m gross, a sum unthinkable in today’s moviegoing climate. Hopper’s middle finger to the establishment struck a chord with a public in thrall of the country’s youth movements, who could relate to Billy and Wyatt’s desire to be and stay wild.

Tapping into that sentiment afforded Hopper and the trailblazers who’d follow his example their own version of the liberty he first prized without romanticizing. After all, as Wyatt mumbles around a lonely campfire, they blew it. Back in the real world beyond the frame, Hopper blew it too, parlaying the film’s popularity into his wrongfully maligned and slowly reclaimed follow-up The Last Movie, a financial failure that killed his career as a director for the rest of the ’70s. But for the summer of Easy Rider, he and his crew could live like their own biker gang, roving around and seeing what there is to see. For a film-maker, a workable budget might as well be a tube of coke money, and final cut rights feel a lot like freedom.

No comments:

Post a Comment