At the twenty-fifth Conference of the Parties (‘COP25’) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (‘UNFCCC’) (see our COP25 explainer here), Australia blocked climate action, along with the usual suspects – e.g. US, Brazil and Saudi Arabia. And China and India were not prepared to step-up up their efforts to tackle climate change, unless the developed countries did so too. They were aggrieved because developed countries are accountable for the lion’s share of historical emissions that are supercharging current extreme weather events around the world and yet many rich, developed countries are not ramping up their responses to the climate crisis.

Despite the best efforts of the Spanish hosts and the Chilean presidency to get the talks back on track and reach agreement on major issues such as carbon markets, positions were too entrenched. At the end of the longest ever COP climate talks, the UN chief said, “the international community lost an important opportunity to show increased ambition on mitigation, adaptation and finance to tackle the climate crisis.”

The gap between what the science says is necessary to tackle climate change and the political response seems like a bottomless trench – so deep that there’s little chance of Santa and his helpers travelling the distance to deliver Christmas goodies.

So, does the Australian Government deserve to be off Santa’s list?

The Australian Government has once again proved itself to be a laggard on global climate action; obfuscating and blocking climate action at a time when we need it most. It was an embarrassment. Facing pressure back home from all walks of life – farmers, emergency leaders, medical practitioners, local mayors to students – the condemnation didn’t dissipate as the Australian delegation was on the global stage at COP25 in Madrid.The only thing that was slightly different about this COP is that rather than simply marching in lock step behind the world’s major climate-denying nations, this year Australia has been at the vanguard.

Climate change requires a concerted global response. And yet the achilles heel of the UN climate process was clear to see in Madrid….decisions are made by consensus, meaning that unless every country agrees on a rule, no rule can be made.

The original due date for the Paris rulebook was at the close of COP24 in Katowice, Poland last year. Considerable progress was made but there were a few key sticking points:

- The rules for international trade in emissions reductions

- The need for all countries to increase their ambition for the next round of emissions reduction pledges

- The need for developed countries to step up on climate finance.

On sticking points, Australia has been a key blocker. And the Australian delegation at the climate talks in Madrid astounded international colleagues by failing to mention climate impacts ravaging Australia just now, such as the devastating bushfires. Instead talking up their climate performance, just when Australia was ranked last out of 57 countries on climate performance.

Tell me more about the market mechanism. What’s happening there?

Get comfy as we unpack this for you…Article 6 of the Paris Agreement is intended to set up a world-wide market for countries to seek out ways to reduce emissions in the cheapest possible way.

Ultimately, to prevent the world from warming further, all use of fossil fuels must stop, and all greenhouse gas emissions must be in balance, i.e. the amount of emissions put into the atmosphere are equal to the amount of emissions being absorbed or captured.

But between now and that point—which climate nerds call ‘net zero’—it may be cheaper for some countries to reduce emissions faster than others. A trade in reductions allows countries such as Singapore where reducing emissions is relatively difficult, to pay for reductions in countries like Papua New Guinea where reducing emissions is relatively easy.

The Paris Agreement allows for the use of international trade in emissions reductions.

This type of trade was also permitted under the Kyoto Protocol. The most frequently used were ‘Certified Emissions Reductions’ (‘CERs’) under the Clean Development Mechanism, which saw the developed world pay for emissions reduction activities in other countries. A lot of certified emissions reductions were issued, but many of the credits were issued against projects that were of dubious integrity.

And here’s the problem. The international community is keen to move on from this era of intolerable doubt over whether traded credits represent what they are supposed to.

The Clean Development Mechanism is a Kyoto Protocol scheme, and wasn’t ever intended to go beyond it. As we push toward 2020, there are several countries holding a glut of credits who are keen to carrying them over into Paris. Brazil and India are among those who are especially keen to do so.

At the end of COP24 last year, the draft rulebook for carbon trading under the Paris Agreement had to be thrown in the bin as countries could not agree over whether to allow in a flood of credits of doubtful integrity.

COP25 Delegates in Madrid, 2019.

What’s Australia got to do with this?

Not content to see Jair Bolsonaro’s Brazilian Government have all the fun breaking global ambition to act on climate change, Australia has gone one further. For everything problematic about the Kyoto CERs, they are at least on paper linked to an emissions reduction effort.The Australian Government’s attempts to bring soon-to-be-expired allocations from Kyoto into Paris is a whole other story and certainly not a crowd pleaser. It’s a long, complicated and difficult to grasp story. So bear with us, but it’ll help you keep track of any climate policy shenanigans.

The type of unit Australia is trying to bring into the Paris Agreement (the global pact to limit global temperature rise and reduce escalating climate risks)—the famed ‘carryover credit’—is not really a credit at all. The better word for it is an ‘allocation’, but the technical term is an ‘assigned amount unit’ (‘AAU’).

These units are essentially a permit to pollute. Each unit gives a country permission to emit one tonne of greenhouse gas. The number a country is linked to its emissions reduction goal. The number a country receives is decided by converting its agreed targets into a quantity of greenhouse gases that can be emitted over the period.

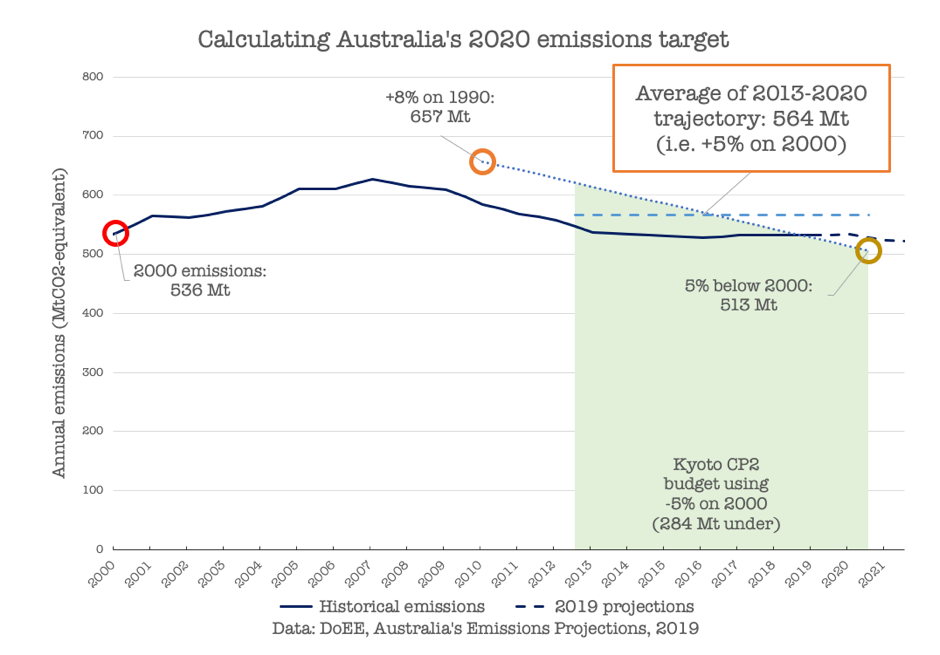

The rules around this are complicated but under them, Australia’s current target—5% below 2000 levels in 2020—results in Australia receiving 4,511,619,826 AAUs. An average of 564 million tonnes per year, every year, for eight years.

In 2000, Australia emitted 536 million tonnes. So under the rules, our 5% below 2000 target becomes a 5% *above* 2000 target for the whole period.

That makes Australia’s target the weakest of all targets in the period.

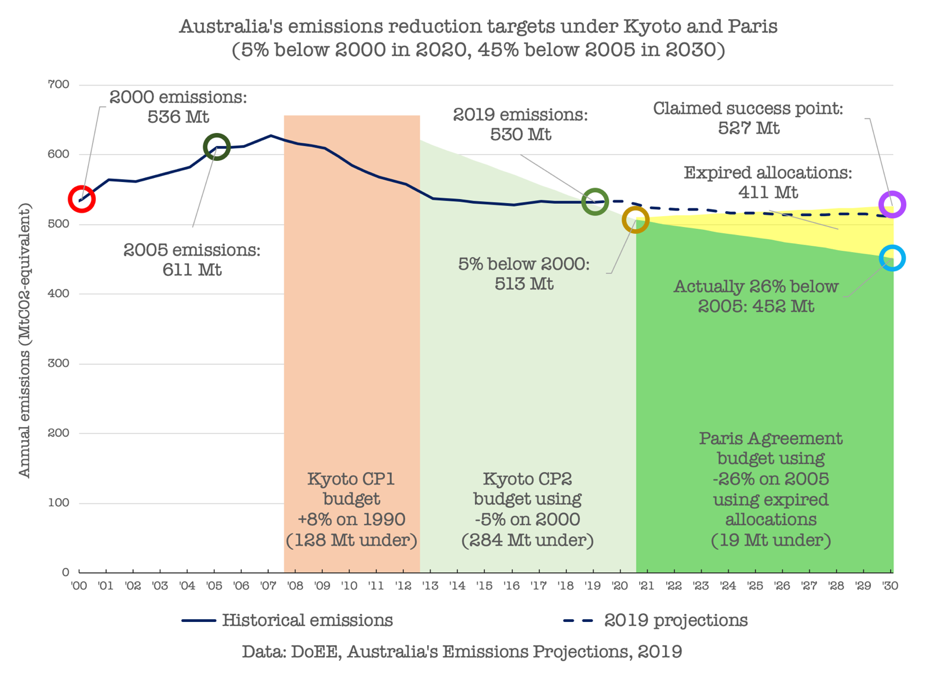

So yes, we achieved the target, but that’s hardly surprising because the bar was set so low. What is surprising is how small this so-called ‘over-achievement’ is under the circumstances. Both of Australia’s targets allowed an overall increase in emissions over the period when compared to the year chosen as a reference point.After these two periods are done and dusted, Australia expects to have 411 million spare AAUs representing emissions we could have released under the second worst (2008-2012) and worst (2013-2020) targets in the world. But didn’t.

And now after successfully negotiating extraordinary targets under Kyoto, the Australian Government is planning to use these expired allocations from an entirely different agreement to undermine the Paris Agreement as well.

It’s not really all that different to trying to use expired vouchers that you got in the mail from Coles at your local IGA. But so much more is at stake.

And unlike the credits being claimed by Brazil, there is no link whatsoever between the units Australia is trying to drag into the Paris Agreement and emissions reductions.

Why is this such a big deal?

This is a big deal because despite what you might have heard, Australia is a big player on the international stage as the 14th highest emitter. In August, the Australia Institute noticed that our claimed accounting fudge was eight times the size of the annual emissions from the entire Pacific including New Zealand. Now that figure has grown, and at 411 million tonnes, it is tantalisingly close to being the same size as a decade worth of emissions from the Pacific. Australia has dodgy tricks that are nearly the same size as the emissions of an entire region.This is a big deal because it turns Australia’s already far too weak target for the Paris Agreement, a 26% to 28% reduction on 2005 levels by 2030, into basically no reduction at all. Emissions in the 2019 financial year were 530 million tonnes. To meet our Paris goal once our dead allocations from Kyoto are carried over, emissions in 2030 need to be 527 million tonnes: half a percent below where they are today. The sunniest and windiest inhabited continent on the planet will no longer be reducing emissions, but simply holding steady as the highest per person emitter among all large countries.

This is a big deal because the only way that these units get into the Paris Agreement is if rules around integrity of pledges and performance are broken. There is no form of carbon accounting with integrity that could deem this genuine.

Finally, this is a big deal because, as a result of Australia’s refusal to take responsibility for reducing emissions, talks on article 6 have again collapsed this year. The ‘compromise’ position reached at the end of COP25 is that the text for the market mechanism cannot be finalised before the Glasgow COP in late 2020—mere weeks before the scheme is supposed to begin.

Because all decisions at COP must be made by consensus, Australia—along with a rump of other bad faith actors—has now ensured that there can be no functioning international carbon market under the Paris Agreement when it begins on 1 January 2021.

This could result in countries all over the world lowering their ambition for the next round of pledges, all because the Australian Government can’t even take responsibility to act on climate change when the country is on fire.

The Federal Government is well and truly off Santa’s list because of its failure to respond to the climate crisis.

No comments:

Post a Comment