The story of the now-defunct Wagin Argus in Western Australia tells a bigger story about Australia’s unfolding regional media crisis

In the great tradition of country towns with unusual claims to fame,

Wagin is home to the second largest ram sculpture in Australia.

The sheep and wheat town, population 1,852, is 230km south-east of Perth. Its 30-foot-tall Giant Ram statue, unveiled in May 1985, held the crown for just four months before it was tragically usurped by the 50-foot Big Merino in Goulburn, which opened in September the same year.

When this history unfolded, the Wagin Argus was 80 years old and thriving. The newspaper went on to celebrate its 110th birthday in March 2015 at the annual Woolorama festival, where its lone 20-year-old journalist accepted a commemorative award.

“We hope to express the district’s hope and expectation that

providence will continue to smile on the good ship Wagin Argus and all

those who sail in her,” the presenter said.The sheep and wheat town, population 1,852, is 230km south-east of Perth. Its 30-foot-tall Giant Ram statue, unveiled in May 1985, held the crown for just four months before it was tragically usurped by the 50-foot Big Merino in Goulburn, which opened in September the same year.

When this history unfolded, the Wagin Argus was 80 years old and thriving. The newspaper went on to celebrate its 110th birthday in March 2015 at the annual Woolorama festival, where its lone 20-year-old journalist accepted a commemorative award.

Six months later, she sank. “Fairfax planning to axe Wagin Argus, Merredin-Wheatbelt Mercury, Central Midlands Advocate” read the ABC headline. The article added, unconvincingly: “The regions will instead be serviced by an expanded Farm Weekly newspaper.”

It was an early event in Australia’s unfolding regional media crisis, now much accelerated as media giants cease to print, or shut altogether, scores of titles in the coronavirus pandemic. And it offers lessons, too – some dispiriting, others hopeful – about what the future may hold for affected towns.

Asked what the Argus meant to them, Wagin locals offer various accolades: “It was the heart of everything.” “My wedding photo was on the front page, a thousand years ago.” “It helped hold the community together.” “It was a very important part of my life.”

The paper covered community events with gusto, scrutinised shire politics and painstakingly documented the local footy, netball and cricket triumphs.

When it closed, “people were very lost, to start with,” says the 38-year-old Wagin ambulance officer Amanda Howell. “I think people relied on it. Every Thursday they knew the Argus came out and that had all the info for the week.”

Veana Scott worked at the Argus as a journalist, editor and photographer for 26 years before retiring in 2009. “I know that sounds rather strange,” she says, “but then we’re farmers in the district and I couldn’t move the farm and I loved my writing and I loved my job and I started just a young journo and finished up as the editor, so I did have a fair bit of power.”

Phil Blight, 62, has been the shire president for the past 12 years. Did he read the Argus? “Every week.” According to Blight, the town has lost a faithful historian.

“I can remember the front page, for example, when Donald Campbell drove through town [in 1964] after having smashed the world speed record in Lake Dumbleyung just down the road,” he says. “That’s recorded now in the archives of the Argus, and that won’t happen again. To me that’s pretty sad.”

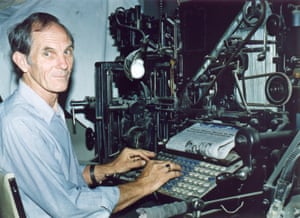

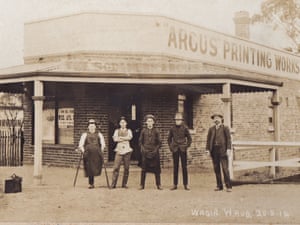

If the Argus was the historian of Wagin, Don and Coral Davies are the historians of the Argus. Don worked there from 1956 to 1999, starting as an apprentice linotype operator and taking over the business – the Argus and a commercial printing press – when his stepfather, the previous owner, died in 1972. Coral handled accounts, took photographs and “anything that needed doing”.

In 1993 Don reluctantly sold to Rural Press, which in 2007 merged with Fairfax, which has since been taken over by Nine.

Now aged 78 and 71, Don and Coral felt so strongly about preserving the paper’s legacy that they staged a low-level heist upon hearing the bound archives had been left behind in the old Argus building when it was sold in 2012.

“I guess we felt like we didn’t have any authority to be doing it,” Coral says. “We just made sure they were safe.”

The Davies look back with great sadness about how things ended.

“One of the reasons we sold out in the first place was because we couldn’t have financed the changes to digital and we knew that Rural Press could,” Don says.

“We sold to preserve it,” Coral adds, “not to have it close down.”

But even as they mourn the Argus, Wagin locals are clear-eyed about its decline.

At its height in the 80s, there were eight people employed across the buzzing newsroom and noisy printing press. By 2014, the paper was staffed solely by Blayde Grzelka, a teenager fresh out of high school who was doing his best at his first media gig. He spent three days a week in Wagin, living in a room at the local pub, and filed to an editor an hour and a half away in Collie. The other two days he filed for the Fairfax paper in Mandurah.

“It might have been a bit too much for me to handle at the time, but I made it work,” Grzelka says.

There were other problems. Advertising in the Argus had plummeted, and the lucrative Woolorama program was basically keeping the paper afloat. Blight recalls making the case for the Argus to a Fairfax executive, and being told to go and count the number of ads in a recent edition. There were five. “I thought, ‘wow, nothing could survive on that’,” he says.

Wagin was an interesting place to cut his teeth, Grzelka says, but he became dispirited after encountering pushback on his attempts to write about mental health. As his career progressed, he struggled to find meaning in his work, and eventually left journalism.

“At the end, when I was reporting there, I don’t think I did a whole lot of good,” he says, of the Argus. “It was just a thing that has always existed there, and they needed it to still exist, and that’s why I was there.”

How are stories in Wagin told now? Some nearby towns still have newspapers owned by Seven West Media. The Narrogin Observer does a good job of covering the area, according to Blight, but it’s not the same. “Not your own town, not your own identity,” he says. “It just doesn’t quite cut the mustard.”

Each time a country paper shuts down there is a ripple effect, spreading out to the smaller towns in its orbit. The Wagin paper used to cover the tiny towns of Dumbleyung and Lake Grace, now the Narrogin paper covers Wagin. “Anything to the east of us, there wouldn’t be a journalist within cooee,” says Coral Davies.

Social media plays a role, with some groups and pages devoted to sharing Wagin events and chatter. Everyone agrees that this leaves out many older people in the area.

“We’re probably halfway between everyone being engaged with social media and no one being engaged with social media, so there’s a vast tract of our community who wouldn’t know what happened last week,” Blight says. As Coral Davies puts it, the paper folded “a generation too soon”.

A front page of the Wagin Argus from 1978.

After the Argus went, the local community resource centre started putting out a newsletter, the Wagin Wool Press.

Jessica Hamersley, 70, is on the volunteer committee. The aim is to fill some gaps left by the Argus: sports news, rosters, other “nitty-gritty” details, and a fortnightly front-page story. Funding is cobbled together from the centre, advertising and sales.

Elsewhere, community-run publications have popped up that fall closer to the newspaper end of the spectrum.

In Merredin, halfway between Perth and Kalgoorlie, the community-run paper is called the Phoenix. It has no journalists, and while a council media manager criticised its quality in a 2019 survey by the Public Interest Journalism Initiative, long-time residents Martin Morris and Brad Anderson say it has plugged the gap, and feels more genuinely local than the Fairfax-owned paper it replaced.

New independent newspapers the Horsham Times and Ararat Advocate have recently sprung up in regional Victoria to replace titles hit by the pandemic closures, as well as the Naracoorte Community News in South Australia.

Hamersley, who used to write for the West Australian, would love to see the Wool Press morph from a newsletter to a full-blown community newspaper – but adds Wagin could use some help. “That would be mighty fine, if somebody would set up some sort of ‘how to be a local journalist’ learning that we could all tap into.”

In the meantime, as papers continue to fold, she is worried. “I think lots of things were happening before the pandemic, and have been exacerbated by the pandemic, that illustrate country Australia is losing its voice.”

No comments:

Post a Comment