A century after the 1918 pandemic, South America’s largest country

has passed Britain to claim the world’s second-highest death toll

As a child growing up in 1940s São Paulo, Drauzio Varella remembers his grandmother’s tales of how the Spanish flu ravaged the blue-collar immigrant community they called home.

“So many people died that families would leave people outside on the pavements, and early each morning the carts would come by to collect them and take them off to burial in mass graves,” remembered Varella, who would go on to become Brazil’s best-known doctor.

More than a century after the 1918 calamity, South America’s largest

country is again being shaken by a devastating pandemic, and Varella is in disbelief.“So many people died that families would leave people outside on the pavements, and early each morning the carts would come by to collect them and take them off to burial in mass graves,” remembered Varella, who would go on to become Brazil’s best-known doctor.

“Nobody thought this could happen. Perhaps they imagined it theoretically – that some kind of virus might come along,” said the 77-year-old oncologist, author and broadcaster. “But even when this virus did show up, we didn’t think it would cause a tragedy of such proportions.”

The precise magnitude of Brazil’s Covid-19 tragedy remains unclear – but the story told by official statistics grows more wretched by the day.

On Friday, Brazil overtook Britain as the country with the world’s second-highest death toll: 41,901 deaths since the first fatality was confirmed in São Paulo on 17 March.

A University of Washington projection indicated another 100,000 Brazilians could die before August, possibly placing Brazil ahead of the US as the country with the most deaths.

As the catastrophe deepens there is growing anger at the conduct of president Jair Bolsonaro, whose jumbled and dysfunctional handling of a pandemic he has called a “fantasy” has made Boris Johnson’s widely panned response look sober and efficient.

“This is the worst public health crisis we’ve faced – and it has come at a time when we have the worst government in the world,” said Daniel Dourado, a public health expert and lawyer from the University of São Paulo who believes thousands of lives could have been saved by a swifter and less erratic response. “The country is adrift.”

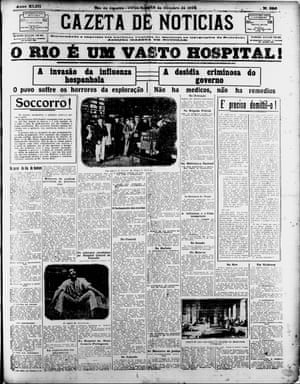

There are uncanny and painful parallels between the impact of the Spanish flu – which historians say killed between 35,000 and 100,000 Brazilians – and the harm coronavirus is now inflicting.

Claudio Bertolli Filho, the author of a book on the 1918 pandemic, said Brazil’s then leaders had initially played down the unknown influenza – just as Bolsonaro has dismissed coronavirus as a “bit of a cold”.

Then, too, authorities tried to hide the true scale of the disaster – just as Bolsonaro’s health ministry has been accused of doing – until, like now, the determination of Brazilian journalists made that impossible.

As the Spanish flu ripped through cities, from Recife to Rio, religious leaders also touted miracle cures just as powerful televangelists today promise followers Covid-19 salvation with holy water and supernatural seeds.

And in 1918, as now, the mysterious malady prompted an explosion of rumour and conspiracy, including claims German submarines had secretly spread the infirmity along the Brazilian coast. (In fact, it arrived on an English merchant ship called the Demerara).

But perhaps no parallel is more cruel than the way in which both catastrophes obliterated the idea pandemics chose victims indiscriminately.

Bertolli Filho said the 1919 death of Brazil’s president-elect, Rodrigues Alves, from the Spanish flu was widely cited as proof epidemics were equal opportunity.

In fact, cemetery records showed most of São Paulo’s 5,000 dead hailed from working class, industrial districts such as Mooca, Ipiranga, and Brás, where Varella’s grandmother watched the corpse collectors at work. Today, the areas suffering most are blue collar communities such as Brasilândia, Freguesia do Ó and Capão Redondo where many do not have the luxury of social distancing or working from home.

In Rio, deprived western neighbourhoods such as Campo Grande, Realengo and Bangu have recorded some of the highest death tolls while densely populated favelas like Rocinha and the Complexo da Maré are also being punished.

“The truth is, not even a pandemic is truly democratic,” Bertolli Filho said.

Varella, who lives in his grandmother’s house to this day, said it was too soon to know just how high a price the poor would pay in a country where the richest 1% control 28% of the wealth.

“Brazil’s situation is so worrying and so unique because if you look at the path the epidemic took – from China, through Asia, and then Europe and on to the US – Brazil was its first encounter with a country suffering from the kind of severe social inequality ours does.”

“It will hit other unequal countries, like India and Pakistan, but here was the first – and we are seeing this play out now in a country where 13 or 14 million people live in precarious conditions and great poverty.”

The omens were not good. “Ever since the epidemic began, I’ve woken up every day feeling afflicted, thinking about what will happen and how,” Varella said.

“The biggest problem we are seeing across Brazil right now is the epidemic spreading through the outskirts of cities and their rundown centres where you have tenements and the homeless live.

“Where this will end we have no clue – no clue at all,” he admitted. “Because we are now right in the middle of the dissemination.”

No comments:

Post a Comment