Extract from The Guardian

Even species we see every day are sliding towards endangerment due to habitat loss

• Vote here in the Guardian/BirdLife Australia 2019 bird of the year poll

• Vote here in the Guardian/BirdLife Australia 2019 bird of the year poll

Across parts of Australia, vast areas of native vegetation

have been cleared and replaced by our cities, farms and infrastructure.

When native vegetation is removed, the habitat and resources that it

provides for native wildlife are invariably lost.

Our environmental laws and most conservation efforts tend to focus on what this loss means for species that are threatened with extinction. This emphasis is understandable – the loss of the last individual of a species is profoundly sad and can be ecologically devastating.

But what about the numerous other species also affected by habitat loss, that have not yet become rare enough to be listed as endangered? These animals and plants – variously described as “common” or of “least concern” – are having their habitat chipped away. This loss usually escapes our attention.

These common species have intrinsic ecological value. But they also

provide important opportunities for people to connect with nature –

experiences that are under threat.Our environmental laws and most conservation efforts tend to focus on what this loss means for species that are threatened with extinction. This emphasis is understandable – the loss of the last individual of a species is profoundly sad and can be ecologically devastating.

But what about the numerous other species also affected by habitat loss, that have not yet become rare enough to be listed as endangered? These animals and plants – variously described as “common” or of “least concern” – are having their habitat chipped away. This loss usually escapes our attention.

The ‘loss index’: tracking the destruction

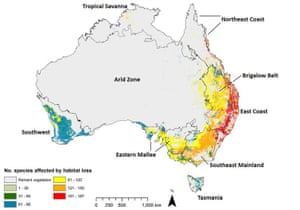

We developed a measure called the loss index to communicate how habitat loss affects multiple Australian bird species. Our measure showed that across Victoria, and into South Australia and New South Wales, more than 60% of 262 native birds have each lost more than half of their original natural habitat. The vast majority of these species are not formally recognised as being threatened with extinction.It is a similar story in the Brigalow belt of central NSW and Queensland. The picture is brighter in the northern savannas across the top of Australia, where large tracts of native vegetation remain – notwithstanding pervasive threats such as inappropriate fire regimes.

We also found that in some areas, such as south-east Queensland and the wet tropics region of north Queensland, the removal of a single hectare of forest habitat can affect up to 180 different species. In other words, small amounts of loss can affect large numbers of (mostly common) species.

Our index allowed us to compare how different groups of birds are impacted by habitat loss. Australia’s parrots have been hit hard by habitat loss, because many of these birds occur in the places where we live and grow our food. Birds of prey such as eagles and owls have, as a group, been less affected. This is because many of these birds occur widely across Australia’s less developed arid interior.

Habitat loss means far fewer birds

Our study shows many species have lost lots of habitat in certain parts of Australia. We know habitat loss is a major driver of population declines and freefalling numbers of animals globally. A measure of vertebrate population trends – the Living Planet Index

– reveals that populations of more than 4,000 vertebrate species around

the world are on average less than half of what they were in 1970.

In Australia, the trend is no different. Populations of our threatened birds declined by an average of 52% between 1985 and 2015. Alarmingly, populations for many common Australian birds are also trending downwards,

and habitat loss is a major cause. Along Australia’s heavily populated

east coast, population declines have been noted for many common species

including rainbow bee-eater, double-barred finch, and pale-headed

rosella.This is a major problem for ecosystem health. Common species tend to be more numerous and so perform many roles that we depend on. Our parrots, pigeons, honeyeaters, robins, and many others help pollinate flowers, spread seeds, and keep pest insects in check. In both Europe and Australia, declines in common species have been linked to a reduction in the provision of these vital ecosystem services.

Common species are also the ones that we most associate with. Because they are more abundant and familiar, these animals provide important opportunities for people to connect with nature. Think of the simple pleasure of seeing a colourful robin atop a rural fence post, or a vibrant parrot dashing above the treetops of a suburban creek. The decline of common species may contribute to diminished opportunities for us to interact with nature, leading to an “extinction of experience”, with associated negative implications for our health and wellbeing.

We mustn’t wait until it’s too late

Our study aims to put the spotlight on common species. They are crucially important and yet the erosion of their habitat gets little focus. Conserving them now is sensible. Waiting until they have declined before we act will be costly.These species need more formal recognition and protection in conservation and environmental regulation. For example, greater attention on common species and the role they play in ecosystem health should be given in the assessment of new infrastructure developments under Australia’s federal environment laws (formally known as the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999).

We should be acting now to conserve common species before they slide towards endangerment. Without dedicated attention, we risk these species declining before our eyes, without us even noticing.

• Jeremy Simmonds is a postdoctoral research fellow in conservation science, at the University of Queensland. Alvaro Salazar is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Queensland. James Watson is a professor at the University of Queensland. Martine Maron is an ARC future fellow and professor of environmental management at the University of Queensland.

• This piece was originally published in the Conversation

No comments:

Post a Comment