Extract from The Guardian

“Sydney’s burning.”

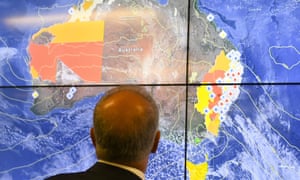

That might be a headline from any Australian media outlet today, given the fires consuming New South Wales (and other states).

But it’s actually the title of Ian Turner’s classic account of the suppression by the Australian government of an international labour union, Industrial Workers of the World, in 1916.

Turner explains how, in an Australia deeply divided by Billy Hughes’s plans for conscription, a series of suspicious blazes provided pretext for draconian repression, with 12 members of the antiwar IWW imprisoned for, among other offences, “feloniously and wickedly conspire[ing] to burn down and destroy buildings and shops in Sydney and elsewhere in the state”.

The story’s one that resonates in a post-9/11 world.That might be a headline from any Australian media outlet today, given the fires consuming New South Wales (and other states).

But it’s actually the title of Ian Turner’s classic account of the suppression by the Australian government of an international labour union, Industrial Workers of the World, in 1916.

Turner explains how, in an Australia deeply divided by Billy Hughes’s plans for conscription, a series of suspicious blazes provided pretext for draconian repression, with 12 members of the antiwar IWW imprisoned for, among other offences, “feloniously and wickedly conspire[ing] to burn down and destroy buildings and shops in Sydney and elsewhere in the state”.

In the last decades, we’ve become accustomed to leaders hyping up supposed threats (most historians consider the charges against the IWW Twelve a crude frame-up) to national security to push through a political agenda that would never be acceptable under normal circumstances.

That’s why, with Sydney on fire once more, it’s worth thinking about how governments respond to terrorism, and how they respond to climate change.

Imagine if Islamic State or al-Qaeda had conducted an attack equivalent in its effects to the current blazes.

If it were terrorists rather than fires responsible for six deaths, the destruction of about 700 homes, and the devastation of 2.7 million hectares, would Scott Morrison have tweeted a picture of himself at the Gabba, cheerily promising terror-impacted communities that “our boys” would give them “something to cheer for”?

Obviously not. We know from previous experience that even a relatively minor security incident utterly reshapes the political landscape. A terror attack on the scale of the current emergency would have transformed Australian politics forever.

Yet that’s not what happened.

The Sydney Morning Herald’s Peter Hartcher recently expressed his bemusement at how little attention was paid during parliamentary question time to the dangerous smoke choking Australian cities. “The politicians talked about a great many things,” he wrote. “But if you watched it on TV, the subtitles were about only one: … a non-stop series of fire alerts … At no point in an hour and a quarter did the politicians discuss the most obvious and pressing concern for most of the people they represent.”

As the world’s media noted, Morrison seemed particularly blasé about the whole business, providing no particular advice or consolation for Australians exposed – potentially for months – to polluted air. He did, however, announce that anti-terror police armed with assault rifles would patrol the nation’s airports over Christmas.

In 2017, Sydney Morning Herald economics editor Ross Gittins declared that there weren’t “many scams bigger than all the fuss we’re making about the threat of terrorism coming to our shores.” He didn’t mean that terrorism wasn’t real, nor that it represented no threat within Australia. But he pointed out that other dangers that posed immeasurably and demonstrably more risk didn’t receive nearly the same attention.

The number of people killed by terrorists on home soil in recent decades remains in single digits whereas, as Gittins says, alcohol kills 15 Australians and hospitalises 430 each and every day. Yet the real (but very slight) threat of domestic terror dominates policy while the real (and very major) consequences of alcohol abuse do not.

The same comparison might be made in relation to climate change, an issue inevitably centred on risk.

“We are on track,” says the UN environment program, “for a temperature rise of over 3C. This would bring mass extinctions and large parts of the planet would be uninhabitable.”

That’s a prediction, not a guarantee (though it’s worth noting that a recent survey of peer-reviewed literature has shown that agreement among research scientists on anthropogenic global warming has effectively reached 100%).

Yet the same politicians who demand action to prevent the most statistically unlikely (but, of course, still possible) terror outcomes seem determined to ride their luck on climate.

Sixteen years ago the report of the inquiry into the 2002-2003 Victorian bushfires warned that “climate change throughout the present century is predicted to lead to increased temperatures and, with them, a heightened risk of unplanned fire” – a finding confirmed by multiple studies ever since.

Professor Dale Dominey-Howes from the University of Sydney puts it like this: “Though these bushfires are not directly attributable to climate change, our rapidly warming climate, driven by human activities, is exacerbating every risk factor for more frequent and intense bushfires.”

Given the disastrous consequences of fires, consequences we’re now experiencing, why didn’t the identifiable (and repeatedly identified) risk from global warming put environmental action, rather than national security, at the top of the political agenda?

Morrison describes climate change as “a global phenomenon” and tells us “we’re doing our bit” to fight it. Anthony Albanese wants higher domestic carbon targets but rejects any suggestion of curtailing coal exports to send a message to other countries.

Yet when it comes to the war on terror, those exact arguments go out the window.

Back in 2003, John Howard insisted on taking the country to war in Iraq, explicitly stressing the moral necessity of showing support for the efforts of America and Britain.

Militarily, Australian troops made little difference to the enormous American force. Politically, George W Bush wanted a developed country to enlist in his ”coalition of the willing” – an alliance including nations such as the Marshall Islands, Palau and Solomon Islands (which didn’t actually have armies).

“Australia cannot,” said Howard, “purchase security by keeping its head down and leaving others to do all the heavy lifting”.

The resulting conflict killed hundreds of thousands of people, devastated the region and cost Australia billions of dollars.

The counterfactual is obvious.

Imagine where we might be if, back in 2003, Bush and Blair and Howard had formed their coalition, not to destroy non-existent WMDs but to pursue decarbonisation. The best recent estimate suggests that the US devoted $1.06tn to the Iraq war.

It’s a staggering figure, a sum that would have gone a long way to fund a just transition to a sustainable international economy. But our leaders chose instead to launch, in the name of fighting terror, a war of choice in Iraq.

The region has been in flames more or less ever since – and now Sydney’s burning too.

• Jeff Sparrow is a Guardian Australia columnist

No comments:

Post a Comment