Interview

Now enjoying a ‘surreal’ life in Florida – the climate’s good for his

Parkinson’s – the veteran comedian talks about fame, fishing and finally

publishing his routines in book form

The old voice you can conjure with your eyes closed, so for the first five minutes or so it’s disconcerting to sit and talk with Billy Connolly.

That familiar electric gruffness has been replaced with something

kindlier and more considered. Getting used to it is a bit like watching

John McEnroe play tennis on the seniors’ circuit – you wait for a moment

that suggests the old unique timing, and it’s all the more poignant

when you catch the sudden ghost of it.

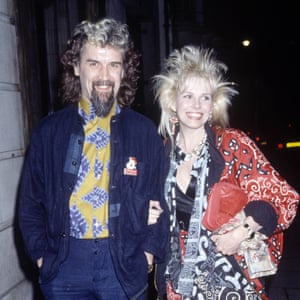

We met in a hotel bar on one of those baking days of summer. Connolly was over in the UK to finish the voiceovers of his latest eccentric tour of America for ITV. His wife, Pamela Stephenson, accompanied him into the coolness of the bar, settled him in a corner chair and then left us to it. All day before we met I’d been immersed in his new book, which collects in print the wild and whirling tales that have been Connolly’s stage show for the past four decades – those riffs on inflight toilets, Mairi’s Wedding, incontinence knickers, the Last Supper. His collected stories. He’s resisted ever writing them down, but the fact that he recently announced retirement from the stage made it seem like the right moment. Still, he says, he can’t quite bear to look at his own words on the page.

If it’s any consolation, I say, it reads like a talking book.

“I hope so,” he concedes. “It’s funny, I tried to write stuff down over the years, but I never could. I’d end up just with things that are good on chat shows, one-liners but no stories. I even tried to write a book once. It ended up two pages long. I couldn’t think of anything else to say.”

"On Twitter, guys I’d never set eyes on were threatening to beat the shit out of me. I thought: fuck this. It’s anti-social media’"

He pauses for a moment, structuring the next thought. “Mind you,” he

says, “one of the best stories I ever read had two pages. This was 50

years ago. Someone in the story had invented a way of linking up all the

computers in the world and it promised to collect all knowledge and

make life amazing for everybody. It fell to the president to launch it.

He typed in the question ‘Is there a God?’ A few seconds went by and the

answer came on the screen: ‘Now there is’.” He pauses again. “And here

we are,” he says.We met in a hotel bar on one of those baking days of summer. Connolly was over in the UK to finish the voiceovers of his latest eccentric tour of America for ITV. His wife, Pamela Stephenson, accompanied him into the coolness of the bar, settled him in a corner chair and then left us to it. All day before we met I’d been immersed in his new book, which collects in print the wild and whirling tales that have been Connolly’s stage show for the past four decades – those riffs on inflight toilets, Mairi’s Wedding, incontinence knickers, the Last Supper. His collected stories. He’s resisted ever writing them down, but the fact that he recently announced retirement from the stage made it seem like the right moment. Still, he says, he can’t quite bear to look at his own words on the page.

If it’s any consolation, I say, it reads like a talking book.

“I hope so,” he concedes. “It’s funny, I tried to write stuff down over the years, but I never could. I’d end up just with things that are good on chat shows, one-liners but no stories. I even tried to write a book once. It ended up two pages long. I couldn’t think of anything else to say.”

"On Twitter, guys I’d never set eyes on were threatening to beat the shit out of me. I thought: fuck this. It’s anti-social media’"

Connolly was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease six years ago, just as he reached his three score years and 10. He got the news on the same day that he was diagnosed with prostate cancer (“You’re not going to die,” the doctor told him. “Of course I’m not going to fucking die,” Connolly replied. “The thought has never crossed my mind”). A timely operation solved the cancer. The Parkinson’s obviously hasn’t gone away. At the beginning of this year he made a film about living with the condition, in which he inadvertently seemed to be saying goodbye. He subsequently had to reassure fans by putting out a short film of himself crooning with his banjo on the deck of his Florida home: “Not dying, not dead, not slipping away.”

“I have good days and bad days,” he says. “Shaky days. I made an arse of it on the film I made, where I said I was wasting away. But Parkinson’s is like that. One day my hearing went, then my balance went, my sight got worse. It feels as if everything is being taken away from you and you watch it go. But I am on medication, so it is all going slowly.”

In his book, he suggests that ever-present sense of decline tends to make you pay more attention to life. Is that so?

“Little changes quickly become normal,” he says. “I can’t get out of bed, so I put my hands up like this” –he raises his arms – “when I want to get up and Pam pulls me to the side of the bed. I can’t get my legs over.” He smiles. “Your priorities change. When I walk into a room now I am scanning to see which chair I might be able to get out of. But it’s not terrible.” He had a doctor who told him: “You have to understand this is an incurable disease.” Connolly corrected him abruptly. “You mean, this is a disease for which we have yet to find a cure.”

“Give me a light in the tunnel for Christ’s sake!” he says. “They are making extraordinary advances. Probably not soon enough for me. But for the next generation, maybe.”

How easy is it to retain a sense that life is comedy rather than tragedy?

Is he a model patient?

“I fear I become a pain in the arse at times. Pamela has to sort my pillows out when I get into bed. She didn’t do it right last night. And you lie there thinking: ‘Can I really ask her to come back and do it again? Or should I put up with it?’ So far, she has never tutted. And she’s a rather attractive nurse.”

It was Stephenson who organised the move to Florida last year. They had been living in New York, but Connolly told her that his uncertain balance couldn’t take another winter of snow and slippery sidewalks. Before he knew it she had found and bought the house in Key West. “And so I went,” he says. “It’s kind of like in my life now, she does things and I follow.”

He has appreciated the move. They have a river that runs by their back door and he can fish off the deck, almost without getting out of bed.

“Manatee come up and I give them water and lettuce,” he says. “These big strange things like mermaids. We have pelicans and turkey buzzards; pterodactyls wouldn’t be a surprise. People drive down to Key West for the sunset and cheer when it disappears over the horizon. Pamela and I don’t cheer, but we watch it.”

There is an alligator catcher, a good man to know. When he catches one he brings it to Connolly’s house first to show him. “His technique is to tie up its jaws and keep it in his garden, where he plays AC/DC to it night and day,” he says. “Motorhead would do just as well – No Sleep ’til Hammersmith. In his experience the alligators just stay away from humans after that.”

Does he feel at home at that end of the earth?

“It’s a good place to live. There are a lot of people running away from regular society: cross-gender people; guys who just fish or lie on the sidewalk. There is a naked bar not far from us, I’ve never been, though Pam has; I told her to choose her bar stool carefully. They are big on parades. Every Tuesday is Tutu Tuesday. It is a surreal kind of place. I like it.”

I have met and interviewed Connolly once before, nearly 20 years ago. At the time he was, at Stephenson’s insistence, facing up to the demons of his Glasgow childhood, what he smiled at calling his “abandonment issues”, enjoying the grandeur of the phrase. He had been having a lot of therapy, not least from his comedian-turned-shrink wife. She had written a book about him, with him, in which he revealed all sorts of darkness. How his mother had literally walked out on him and his sister when they were toddlers and they were apparently by themselves for some days before being discovered and reluctantly taken in by aunts. How his father, not long home from the war, often drunk, had “interfered with him”, abused him over a period of years, experiences that had, he had come to understand, fuelled his own alcoholism. At the time we spoke, he had long been sober but seemed quite high on Californian introspection. Watching him on TV in recent years, I suggest he seems to have parked that phase, moved on from it.

Stephenson – with whom he has three daughters, as well as a son and daughter from his first marriage – was obviously a gift in that regard: a blast of up-front Aussie courage to uncover all that was buried under layers of tight-lipped Scottishness and maleness and old-school Clydeside welder’s banter. She also insisted Connolly had to move forward. “That kind of past is like a big rucksack full of bricks,” he says now. “You can lug it around all your life if you like. Or you can find a way to put it down and walk away.”

He refused to see himself as a victim. “I see people on daytime talk shows, and there is a line underneath saying how sexual abuse or whatever has ruined their life. I think it’s a crime to say that of someone. It makes them a victim of something they are totally innocent of. I don’t dwell on any of that in my past now. I don’t do therapy any more, because I don’t feel I need it.”

Part of the way out of for him was Buddhist meditation. I remember him joking to me the last time we met about how he had recently experienced the ultimate Hollywood moment: Shirley MacLaine had come up to him at a party to whisper how “centred” he looked. Has he kept his practice up?

“Aye,” he says, with a beatific smile. “The mindfulness of breathing. I do it every morning, just to get me squared up.” He catches some of the old Govan cadence. “It is dead easy. You just breathe and make yourself aware of breathing.” He likes the fact it is called “Just Sitting”. “Loosen your trousers, untie your shoes and just sit with your eyes closed for 10 minutes or so. Open the window a wee bit, so you can hear a few noises.”

“It does. Mostly it helps you to not be afraid of yourself. Quiets the voices in your head. And I have plenty of them. Good ones and bad ones, just like everyone else.”

What was the happiest time of his life? I wonder.

“It is all just about now. But getting famous was good. It was like going up a helter-skelter backwards. You know, the first time I had a sell-out at the London Palladium? That’s very exciting. Particularly when you are on your own out there, I think, and it is your own material. You have created this thing and people like it. That was a lovely thing. But being famous gets wearing, though you learn to live with it.”

He is famous in America as much for his film acting as his comedy. I wonder when was the last time he walked into a room and no one recognised him?

“A long time ago. But it’s fine.”

I mention something I remember Tom Waits saying to me on this subject once, in an interview, how “the odd thing about this life is that you spend half your time trying to get people to listen to you and the rest of the time trying to get them to leave you the fuck alone…”

He laughs. “Tom came to see me a few times in San Francisco,” he says, “and he brought his sons along to a show. He called me afterwards to say that he’d had to pull the car over on the way home, and tell his boys that they shouldn’t say ‘cunt’ in front of their mother when they got home.” He adopts a guttural Waits voice: “‘Just because Billy Connolly said it, that doesn’t make it right.’”

It would be fair to say he has never tired of the joys of invective. “I have two grandchildren, 18 and 13 now,” he says. “I used to love it when they were wee and had exercises at school and you’d to talk about your granddad. Wally wrote ‘My granddad has a purple beard and he plays the banjo and he squares [sic] all the time and he also has a big knife – a dirk – which he lets me play with.’”

When he talks about his family the wattage of his attention brightens. “My eldest daughter makes films. She won a prize at Sundance recently. My son Jamie is nearly 50. He and I fish together. He’s brilliant, better than me.”

In his book he writes movingly about how all fathers should go fishing with their sons; unlike with football there is not much action to fill the silence. “You have to talk, you are away for hours, days. And you have to talk to each other. About real things.”

Beyond those pictures Connolly’s relationship with social media is “deliberately sparse”. He has a phone and he can do email. He doesn’t know what Facebook does. He went on Twitter once when he was doing a play with Eric Idle and they were invited to create accounts to promote it. It was like the whole world turned into the Scottish tabloid press.

“Straight away, people just started attacking me, challenging me to a fight. Guys I’d never set eyes on saying they would beat the shit out of me. I thought ‘Fuck this’. It was like being in jail.” He erased it sharpish. “It’s anti-social media,” he says.

He doesn’t see that many “show business” friends these days, he says, though if singers and songwriters he likes – John Sebastian, Arlo Guthrie – are in Florida he will make an effort to go. When he watches people up on stage does he still have a yearning to be up there too, in his element?

“No, I don’t miss it,” he says. “It was great, but life without it is just dandy. Jamie and I were away fishing in Utah a couple of weeks ago. The Green River. We got to know all the guides, and we’d go for dinner with them. A couple of times, I just sort of took over and told funny stories, and it felt great, and they were all roaring with laughter, Jamie too. It was a lovely feeling. Just letting it roll like that again. But no, I don’t miss touring.”

He doesn’t watch much comedy, he says. He always feared he would subconsciously steal stuff and old habits die hard. His heroes are musicians not funny men. “Hank Williams and Bob Dylan are the two,” he says. He has met Dylan a few times, “though each time I have to be reintroduced to him, then we are like best buddies by the end of the evening.” It was when he heard Dylan say he loved Hank Williams, too, that he knew that “there was a God”. Connolly, of course, started out as a singer and banjo player in folk clubs, and “folkies always wanted to look down on country and western music – but not me.”

Does he remember the first time he heard Hank Williams?

One of the highlights of his latest TV travels in America was to pitch up in Alabama and hold Hank Williams’s guitar. He laughs. “I sat there with this wonderful thing, and everyone watching, and of course my mind went blank and I couldn’t think of a single fucking Hank Williams song.”

The theme of that series was going to be Scots in America, “talking to witches and so on” but it didn’t quite work out like that. I wonder if he had planned to do anything on President Trump’s mother, that bouffant émigré from the Isle of Lewis.

“No, we kept away from all that madness,” he says, stiffening. “Talk about Trump, though, look who you’ve got now over here: fucking soft boy.” It’s a relief to be a few thousand miles away from Brexit, he says. “What a con, and the prime minister was the biggest con of all. I saw on American TV people being interviewed in south Wales, and how pleased they were to have voted out of Europe. And then they showed all the things that the EU had funded in their town. They had no idea. It’s completely nuts.”

Connolly has a foot in Europe with a house on the island of Gozo, off Malta, which he bought after his manager, Steve Brown, moved there. Brown died in 2017. He still goes when he can. “We have an old school house. They are lovely people. There are a few Brits there too, mostly moaning about how Britain is full of immigrants…”

He himself has lived away from Scotland, in the States, for a long time now. Is he the kind of expat who needs to have bits of home with him?

“It’s OK,” he says. “The local supermarket has Irn Bru and Tunnock’s caramel wafers.” He is going up to Glasgow after our interview. “I mostly look forward to the curry these days,” he says, “Mother India on Sauchiehall Street. You get a lot of Mexican food in Florida, which always seems to be more about folding than eating.”

Now this book is out, I ask if he has any plans to write a proper memoir.

He admits to “ticking the idea” but that “there’s plenty of other things to do. I’d like to write songs again. I like to draw.” He pauses, and seems a bit weary suddenly. “Life is a bowl of cherries,” he says.

Does he have gloomy moments?

“I do. I sometimes try to visualise what is going to happen to me and then I have to work hard at coming out of it.”

What is the best strategy for that?

“It usually ends up with me saying: ‘Billy, you are 76 years old, how the fuck did you imagine you were going to feel?’”

He thinks again about the question I asked earlier, about happiness. “People think you have to be happy, you know the sun shining and the beach ball and ‘ha ha ha’, but I’ve never been like that. If you change the word happy to content, that’s more what I’m after. When the sun goes down each night, I’m pretty content,” he says, and pauses. “Mind you I sleep like a wild animal these days. Laughing and singing, or having fights. Pamela has to sleep in another bed.”

He thinks those disturbed nights are probably to do with the Parkinson’s or the medication. But he seems to me for the most part, I say, to be going on pretty well.

“I am, and then I’m not. A shudder comes over me and I can’t get my money back in my wallet or whatever.” The compensation, he says, is that it brings out the best in people he meets. “If you say ‘I can’t get up, could you help me out of my chair please?’ no one ever says ‘Why?’ They just do it. Maybe it’s just me but I live in this magical life.”

I suggest that he has worked pretty hard for that over the years.

“I don’t know about that,” he says, and pauses a final time. “I walk down the street and people shout: ‘Hey Billy, how’s it going?’ It’s great,” he says. “I always get the best of people: when they walk toward me they are already smiling.”

• Tall Tales and Wee Stories is published by John Murray Press (£20). To order a copy for £17.60 go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £15, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99

No comments:

Post a Comment