Extract from The Guardian

Exclusive: data from Ceduna, one of the trial sites the Coalition wants to make permanent, finds the card has had ‘no substantive impact’

Last modified on Fri 13 Nov 2020 03.32 AEDT

The cashless debit card has had “no substantive impact” on crime, gambling and drug and alcohol abuse in one of the trial sites the government wants to make permanent, according to a new study.

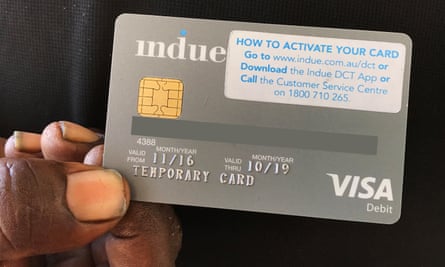

Aimed at reducing social harms in areas with high welfare rates, the scheme quarantines 80% of a person’s payments onto a card that cannot be used to withdraw cash and blocks alcohol and gambling transactions. The card has been predominantly trialled in areas with high Indigenous populations.

In what is the latest independent study to cast doubt on the scheme, four researchers from the University of South Australia and Monash University obtained and examined administrative data from Ceduna, South Australia, where the card has been running since 2016.

“We found no substantive impact on measures of gambling, drug and alcohol abuse, crime or emergency department presentations,” said Dr Luke Greenacre, a business academic from the University of South Australia.

The study comes as the government tries to win support for a bill to make the card permanent in Ceduna, the East Kimberley and the Goldfields areas of Western Australia, and Hervey Bay and Bundaberg in Queensland – all areas with significant Indigenous populations. It would also introduce the card to the Northern Territory. A similar program, the basics card, has operated in the NT since the Howard government’s intervention in 2007.

But taking into account seasonal trends, the researchers found “no pattern” in apprehensions for public intoxication between July 2015 to March 2018. They noted the statistics were “not impacted” by the introduction of the card.

This data was used as a “proxy”, given no “pre-existing dataset shows drug and alcohol consumption during the trial period”.

While gambling levels were “horrifyingly high” when the card was introduced, Greenacre said, the scheme still had “no significant effect” on gambling revenue. That was according to data from January 2014 to December 2016 covering several venues in and near the trial area.

The researchers also obtained local police statistics between July 2012 to September 2017. They found crime levels in the Ceduna area were “low” before the card was introduced and “overall, monthly crime rates remained stable and were not significantly affected by the [cashless debit card]”.

Five years’ worth of hospital data to June 2018 told a similar story, with the academics noting “minimal” change in the number of presentations to the only emergency department in the Ceduna area.

The researchers did find an increase in healthy food sales when they analysed weekly sales data from the sole store in a remote Aboriginal community where 80-90% of the approximately 100 residents were estimated to be on the card.

However, they noted a “greater increase in spending on less healthy (discretionary) food items”.

Greenacre said the study was not designed to examine the “moral” questions around the card, and noted there may be “individual benefits” for particular families that were not picked up by quantitative research.

But he added: “From the more quantitative, economic, whole of community perspective, it suggests the card offers very little, if no return on investment.

“In other words, the cost of implementing and administering the card isn’t producing substantial community benefits such that we’re getting bang from the tax dollar buck.”

The University of South Australia and Monash paper is likely to only further fuel debate about the evidence behind the card as the Senate prepares to consider making the trial sites permanent.

Since 2015-16, the government has spent $80m on the scheme, yet the only government-commissioned evaluation of the program was found by the audit office to be so flawed it was “difficult to conclude whether there had been a reduction in social harm”.

Meanwhile, other academic research has found the card caused “stigma, shame and frustration”, as well as practical issues such as cardholders simply not having enough cash for essential items.

The audit’s findings did little to puncture the government’s faith in the program, though it did prompt it to commission a second evaluation from the University of Adelaide.

Though the government has received a final draft of that evaluation report, it is unclear whether it will be released before the Senate votes on the future of the program.

Last month, the social services minister, Anne Ruston, was accused of seeking to rewrite history when she claimed the final evaluation was “never the premise for deciding the success or failure of the cashless debit card”.

A spokeswoman said the department had not received the final evaluation report. She did not comment on the University of South Australia and Monash University study.

The Department of Social Services briefly summarised its findings in a submission to a Senate inquiry examining the card.

The unpublished final evaluation was said to have found “consistent and clear evidence that alcohol consumption has reduced since the introduction of the CDC”, as well as “short-term evidence” the card was “helping to reduce gambling” and improve financial management.

Guardian Australia reported this month that the more than 100 submissions to the inquiry were overwhelmingly opposed to the government’s bill.

No comments:

Post a Comment