Extract from Eureka Street

- Andrew Hamilton

- 29 October 2020

If society were a mine, refugees would be the canaries in it. Their condition reveals whether the currents of public air are pure or toxic. By that standard the present currents in Australia are noxious. They mark a change from the first generous response to the coronavirus to the meaner reconstruction of the economy.

Initially the government acted decisively for the common good. It shut down economic activity and limited some individual freedoms in order to save lives and protect public health, and supported people whose livelihood was threatened by the shut down. People responded generously.

Now, however, as attention turn to how we can live with the virus, the focus on the common good has given way in many Western societies to demands from different groups to serve their particular interests by opening economic activity. Respect for persons and the common good has been sacrificed to individual freedom in the name of economic growth. The result in the United States and Europe has been the uncontrolled spread of the virus, economic stagnation and an increasingly alienated population.

As Australia prepared to revive economic activity while living with the virus, it could have based the recovery on respect for persons and the common good, or on an economic expansion in which people are measured by their economic usefulness. The government’s treatment of refugees is a guide to which path it has chosen to take. Its vision of the place of refugees in Australian economic recovery as expressed in the Budget and elsewhere is not encouraging. In a world-wide crisis the Budget cut by almost a third the number of refugees and people accepted from overseas.

The same emphasis on narrowly construed Australian needs is evident in foreign aid. Existing foreign aid programs will receive no extra funding, though welcome funding is given to respond to COVID in Timor Leste and the Pacific. Effective aid programs in impoverished nations in Asia and Africa, however, are likely lose their support. This restriction and narrowing of focus in aid seems to reflect a self-interested concern about China’s activity in the region more than the needs of vulnerable people.

The attitudes of the government to refugees are most clearly shown in the treatment of people who have sought protection from persecution in Australia. The support available to people living in the community will be cut by half from last year’s budget to $20 million. Over three years the amount allocated has fallen from almost $140 million, mainly by denying services to people in need. During the coronavirus crisis charities have already seen a massive rise in applications for help from people who have lost jobs and have been denied any government assistance.

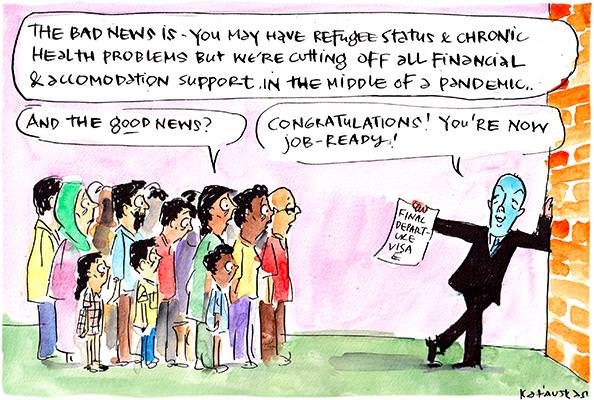

The people most severely affected by the withdrawal of government support are those who some years ago were transferred from Manus Island and Nauru to Australia because of severe health issues. The group, which includes many families with children, were housed in government facilities and received a living allowance but were forbidden to work or study. Earlier this year the Department of Home Affairs decided to close this program. People would have to leave their accommodation and all income support, but would be able to work. They must also leave Australia in six months. In the last month it has begun to enforce these changes that will affect about 500 people, giving people three weeks notice to find accommodation and work.

'The harsh treatment of refugees has made it easier for governments to discriminate against other groups in the community. To expect people to venture into this noxious air in order to rebuild an economy is a big ask.'

Finally, more money will be available to meet the massive costs of offshore processing and expanding the detention centre on Christmas Island. Australian detention centres will continue to house people for year after year. Although the government failed in its bid to strip people detained there of their mobile phones, they remain prevented from receiving visitors during the COVID threat, and their mental and physical health continues to suffer.

When seen from the perspective of the people affected by them, these changes pile misery on misery on top of that caused by the coronavirus. Like other people In Australia, those who seek protection have struggled with the threat that COVID has posed to their mental and physical health. The elements in their struggle include unemployment, loss of the little support they might have received, anxiety about their welfare and that of their families, and the restrictions on movement and association imposed in lockdown and detention.

In addition, they have shared none of the supplementary income provided to help them deal with these afflictions. Now many of them will join many other Australians who enter the ranks of the homeless and unemployed, but they alone will be stripped of all support. It takes little empathy to imagine particularly the anguish and despair of people who have been excluded from education, English courses and working experience in Australia, with no connections in the Australian community, and in poor health, as they enter this new world, and have the added anxiety of being liable to exclusion from Australia in six months. The effects of this on children and their families, on their human spirit and their resilience can only be guessed at.

Seen from the perspective of the government these changes will justify the rightness of its view that people who seek protection are not Australian, are not entitled to any of the rights and privileges of other Australians, might properly be driven from Australia by hardship and deprivation, and be made to suffer conspicuously in order to deter other people from seeking protection and so to justify those responsible for the policy. People who seek protection are not persons with faces but a category, not subjects of their own lives but objects of policy to be handled and discarded. They are not entitled to respect.

Seen from the perspective of humane observers these changes might be seen as vindictive. The plight of people affected will arouse their compassion and anger. The changes lack the respect owed to any human being. They reveal a government that is not concerned for the common good based on respect for a shared humanity, but privileges the humanity of some chosen human beings at the expense of others.

This partiality has been evident also in other areas of government policy in response to COVID-19. Its exclusion of overseas students and university teachers from benefits was not based on economics or on need but on political prejudice against them. The harsh treatment of refugees has made it easier for governments to discriminate against other groups in the community.

To expect people to venture into this noxious air in order to rebuild an economy is a big ask. The dilemma for governments is that people’s confidence to spend will depend on their confidence that they are respected and that the common good is being served. The treatment of refugees corrodes the trust needed for people to look beyond their own security and to spend freely. If the government does not show respect or look to the common good, how can it reasonably expect people to follow its exhortation to spend generously rather than its mean example?

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street, and writer at Jesuit Social Services.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street, and writer at Jesuit Social Services.

No comments:

Post a Comment