Extract from The Guardian

Environmental investigations Environment

The extremes of the past year will soon become commonplace, as rivers dry and temperatures rise

Last modified on Sat 14 Nov 2020 06.01 AEDT

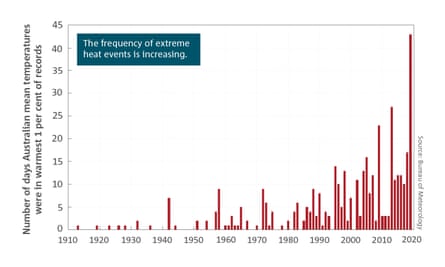

Since 1910, Australia has warmed by 1.44C and the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere have been accelerating.

Neither of those facts would be tangible or noticeable for the everyday Australian.

But as this week’s State of the Climate report has revealed, those intangibles are now delivering the kind of searing temperatures, heatwaves, unprecedented bushfires and shifts in rainfall that mean the climate crisis has undeniably arrived.

What is even more sobering are the warnings in the report that there is, unfortunately, a lot more where that came from.

Here are five big issues the State of the Climate report revealed.

Temperature extremes beyond anything on record

In the 58 years from 1960 to 2018, there were only 24 days where the average maximum temperature across the whole continent hit 39C or higher.

In 2019 alone, there were 33 days.

For some, Australia warming by 1.44C since 1910 might seem benign. But that area average manifests in temperatures that melt roads, thongs and dramatically raise the risk of deadly bushfires.

Dr Karl Braganza, manager of climate environmental prediction service at the Bureau of Meteorology said modelling has been forecasting the changes in temperature and shifts in rainfall for decades. What has changed is that Australians are now starting to feel the affects of those rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns.

Australians are used to living in a climate that is highly variable, with big shifts in temperature and rainfall, he said. But now, they are noticing the extremes.

“When that natural variability and the underlying warming trends push in the same direction, that’s when you break record,” he said.

“In Australia, once you start to push into the 40Cs, that’s extreme by anyone’s measure and in an Australian context, we notice that.”

This is just the beginning

There’s a sense that the year 2019 will live long in the memory of Australians – the hottest and driest year on record where towns ran out of water and bushfires destroyed thousands of homes and killed or displaced billions of native animals.

That year bookended the hottest decade on record.

But the State of the Climate report’s projections suggest that even with ambitious cuts to greenhouse gases, 2019 will be seen in the decades to come as just an average year.

“This is us on a journey,” says Dr Jaci Brown, director of CSIRO’s Climate Science Centre. “This decade will likely be the coolest decade of the next century.”

The Paris climate agreement’s more ambitious goal of keeping global heating below 1.5C is, based on the pledges made by countries, so far well out of reach.

If the world did manage to keep temperatures down to 1.5C, that extra warming would render the heat of 2019 as just your average Australian summer.

The State of the Climate report says that whatever happens to emissions in the next decade “the amount of climate change expected … is similar under all plausible global emissions scenarios”.

“The average temperature of the next 20 years is virtually certain to be warmer than the average of the last 20 years,” the report says.

So what’s in store?

According to the report, Australia will get hotter with more heatwaves and more extreme hot days, the sea level will keep rising as the oceans gather more heat and ice sheets and glaciers melt, and rainfall in southern and eastern Australia keeps dropping.

Less water flowing through rivers

Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology has a network of 467 water gauges in rivers and streams across the continent, and most of them show there’s less water flowing through Australia’s rivers in the south.

Some 222 of those gauges have been recording the flowing water for more than 30 years in places unaffected by irrigations and dams.

According to the State of the Climate report, three quarters of those long-term undisturbed gauges show a drop in riverflows which, the report says, is “an indicator of long-term impacts from climate change”.

Mark Lintermans, an associate professor at the University of Canberra and a freshwater scientist, says this is all “bad news for fish”.

Australia’s native fish are already in trouble, with river systems dramatically altered by irrigation and dams.

Less water flowing through rivers, Linterman says, means they heat up more and sediment tends to build up instead of being washed through.

“Permanent streams can become ephemeral, oxygen levels drop, sediment levels rise, water temperature goes up and the fish get smothered and cooked,” Lintermans says.

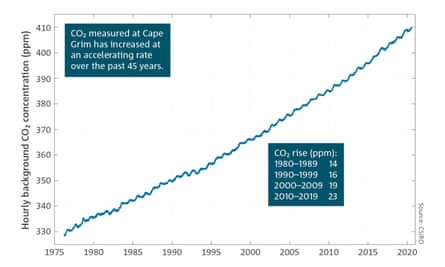

CO2 levels are accelerating in the atmosphere

On the northwest tip of Tasmania at Cape Grim, a cliff-top monitoring station has been measuring the composition of the clean air blowing from the Southern Ocean since 1976.

Dr Zoe Loh, a senior research scientist at CSIRO, leads a team working on the Cape Grim data.

The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere measured at Cape Grim has risen from 330 parts per million when the station opened, to 410 ppm now.

“That’s a really considerable rise and it’s happening at an accelerating rate,” Loh says.

“Through the 1980s the record showed an increase of 14 parts per million. Between 2010 and 2019 [it] rose by 23 parts per million.”

CO2

molecules have different chemical signatures depending on their

origins, and Loh says that analysis shows the rise in atmospheric CO2 is

being “overwhelmingly driven by fossil fuel emissions with some

contribution from land clearing”.

She said ice cores drilled in Antarctica contain bubbles that record the composition of the atmosphere over thousands of years, showing CO2 had been relatively stable at about 278ppm.

“It is very clear that the rate of rise of carbon dioxide we have experienced over the last 100 years is more than an order of magnitude greater than the rate of change in the global atmosphere on a geological time scale.

“We’re now in an era where we are seeing a 10 parts per million rise in three or four years,” Loh says.

“That’s

what’s driving the warming climate and driving all the impacts and the

compounding effects. This will be very hard for us to live with and

adapt to.”

Australia’s oceans are getting hotter, and they’re rising

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef – the world’s biggest coral reef system – has been through three mass bleaching events in the past five years.

The cause of the bleaching is the heating of the oceans and the marine heatwaves that go with it.

As the State of the Climate report notes, eight of the 10 warmest years on record for the country’s oceans have occurred since 2010.

This, the report says, “has caused permanent impacts on marine ecosystem health, marine habitats and species”. The Great Barrier reef and Ningaloo Reef have both suffered.

But the area heating up the fastest is around the southeast and in the Bass Strait off Tasmania, where kelp forests have been disappearing.

“Climate models project more frequent, extensive, intense and longer-lasting marine heatwaves in the future,” the report says.

About 90% of the extra energy caused by the extra greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is taken up by the world’s oceans.

That warmer water is expanding and, with the ice sheets and glaciers melting, the sea level is also rising.

Jaci Brown said globally, sea levels had risen by 25cm since 1880. She encouraged Australians to head to the beach and take a “handy school ruler”, stand at the high tide mark and see how much further the water would travel.

“But even more confronting,” she said. “What would a metre of sea level look like?”

According to the report: “Rising sea levels pose a significant threat to coastal communities by amplifying the risks of coastal inundation, storm surge and erosion. Coastal communities in Australia are already experiencing some of these changes.”

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment