Extract from The Guardian

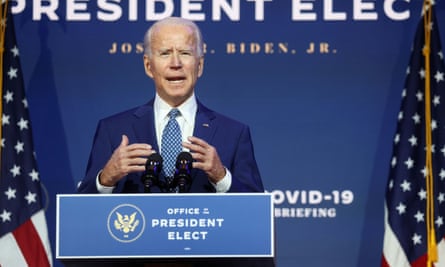

Joe Biden has vowed to return US to Paris agreement and result brightens prospects for Cop26.

Preparations for the next vital UN summit on the climate – one of the last chances to set the world on track to meet the Paris agreement – have been given a boost by the election of Joe Biden as president.

The election caps a remarkable few weeks on international climate action, which have seen China, the EU, Japan and others commit to long-term targets on greenhouse gas emissions to fulfil the Paris climate agreement.

Biden has vowed to return the US to the Paris agreement, from which Donald Trump withdrew, and to set a goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050, commitments that were underlined by his references to the climate crisis in his speeches after the result became clear.

“With Joe Biden elected, what is indispensable can now become possible,” said Laurent Fabius, the French foreign minister who oversaw the 2015 Paris agreement, now president of France’s Constitutional Council. He told the Guardian: “We shall have the conjunction of the planets which made possible the Paris agreement. Civil society, politics, business all came together for the Paris agreement. We are looking at the same conjunction of the planets now with the US, the EU, China, Japan – if the big ones are going in the right direction, there will be a very strong incentive for all countries to go in the right direction.”

That brightens the prospects considerably for the next UN climate summit, Cop26, which would have taken place this week, in Glasgow, had the Covid-19 pandemic not forced a postponement. The talks will take place just under a year from now, and negotiations have continued apace, though hampered by countries’ need to deal with the pandemic crisis.

The re-entry of the US into the Paris fold, and Biden’s proposals for a green economic rescue from Covid, cap a remarkable few weeks of international climate action. Leading nations have made a spate of commitments that have transformed the prospects for Cop26: countries responsible for more than half of global emissions and two thirds of the global economy are now committed to net zero emissions by mid-century – the goal that scientists say is vital to avoid the worst ravages of climate breakdown.

China surprised the world in late September, when President Xi Jinping told the UN general assembly that his country would reach net zero emissions by 2060 and cause its greenhouse gas production to peak by 2030. While details of how Xi intends to achieve this are scant, the plan by the world’s biggest emitter was hailed as a “game-changer” by climate diplomats.

After China’s announcement, Japan’s new prime minister also committed to net zero by 2050, and South Korea followed suit. The EU also reconfirmed in September its net zero goal for mid-century, under the EU green deal.

With China, the US and the EU now broadly aligned, and dozens of smaller countries also committed to net zero plans, success at Cop26 looks possible. But there are still key stumbling blocks.

The crucial issue will be the difference between the long-term targets for reaching net zero emissions by mid-century, and the shorter term targets needed to get there. With the long-term targets in place, attention will turn to the commitments countries are making to reduce emissions in the next decade.

Under the Paris agreement, nations are committed to holding global temperatures well below 2C above pre-industrial levels, with an aspiration to limit heating to 1.5C. To do this, when the agreement was signed in 2015, countries set out national plans – called nationally determined contributions – for cutting emissions by 2030, or similar dates.

Those plans were insufficient, and would lead to 3C of warming. The accord stipulates that every five years countries must put forward fresh targets, and the deadline for those NDCs now looms. Some countries will miss the deadline – Biden cannot make commitments until he takes office in January, and China is still finalising its five-year economic plan for next spring, and so may delay – but the UN is hoping that all will be ready in time for scrutiny ahead of the rescheduled Cop26.

The Guardian understands that the UK, which as host of Cop26 needs to set an example, intends to submit its NDC before a key meeting that Boris Johnson will chair, with the UN secretary general Antonio Guterres, in a month’s time. The Climate Ambition Summit on 12 December will mark exactly five years since the gavel came down on the Paris agreement, and is intended to galvanise action on the NDCs.

That meeting will be a key test of Johnson’s climate diplomacy. Biden will not be present at the summit, as the Trump administration will still be in office. Trump will be invited, but it is not known whether he intends to attend. It will be Johnson’s first stint as host of a major international summit, and a dry run for both Cop26 and the UK’s G7 presidency next year, which is also expected to focus on the climate and the need for a green recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Johnson’s prospective relationship with Biden, proudly Irish-American, has come under the spotlight in recent days, particularly on Biden’s stated concerns over the safety of the Good Friday agreement under Brexit. However, those differences are unlikely to have a strong impact on the climate summit’s success, according to Tom Burke, co-founder of the green thinktank E3G and a veteran government adviser.

“Biden’s victory will be a boost and I don’t think Boris Johnson’s relationship with him will make much difference to that,” he told the Guardian. “There is no difference between the interests of Johnson and Biden on Cop26 – they both know they have to make progress, irrespective of whether there is a falling out over Northern Ireland. They will still work together on the climate, and only the vaporous will conflate the issues.”

No comments:

Post a Comment