Climate agencies say fossil fuel burning is driving the increase of dangerous bushfires and days of extreme heatwaves

Last modified on Fri 13 Nov 2020 03.32 AEDT

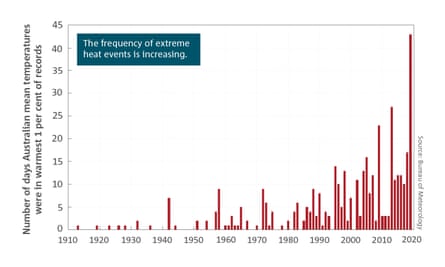

Australia’s climate has entered a new era of sustained extreme weather events, such as dangerous bushfires and heatwaves, courtesy of rising average temperatures, a new report by the nation’s two government climate science agencies has found.

Rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, mostly from fossil fuel burning, has driven more dangerous bushfires, rising sea levels and a rapid rise in the days where temperatures reach extreme levels, the Bureau of Meteorology and the CSIRO said in Australia’s latest State of the Climate Report.

“What we are seeing now is beyond the realm of what was possible previously,” said Dr Jaci Brown, director of CSIRO’s Climate Science Centre.

While 2019 was Australia’s hottest on record that helped deliver unprecedented bushfires, those temperatures would be seen as average once global heating reaches 1.5C, the report said.

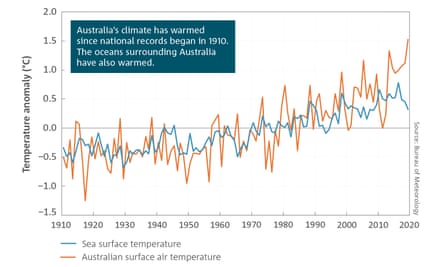

Among the key findings, the report said Australia’s climate had warmed by 1.44C since 1910 with bushfire seasons getting longer and more dangerous. Australia’s oceans had warmed by 1C and were acidifying.

In a briefing to reporters on Tuesday, Dr Karl Braganza, manager of climate environmental prediction service at the bureau, said conditions in Australia were in line with projections over recent decades.

But he said: “What we are seeing now is a more tangible shift in the extremes and we are starting to feel how that shift in the average is impacting on extreme events.

“So we don’t necessarily feel that 1.44C increase in average temperature, but we do feel those heatwaves and we feel that fire weather.”

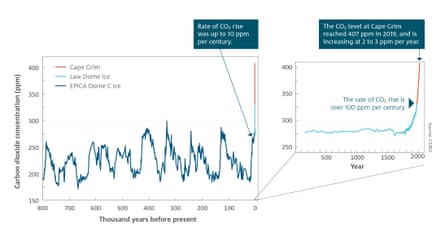

Australia’s long-term greenhouse gas monitoring station at Cape Grim, on the northwest tip of Tasmania, showed levels of CO2 were accumulating on the atmosphere at an accelerating rate.

From 1980 to 1989, the amount of CO2 rose by 14 parts per million, but in the decade ending 2019 the amount rose by 23 parts per million.

Brown said while the global economic slowdown from the Covid-19 pandemic had seen a slowdown in emissions, this was just a blip.

“Another way to think about this is if you have been eating junk food for 10 years and then you go on a diet for one day and jump on the scales the next morning and expect to see some change or drop a dress size. It’s not that simple. This is about a long-term change,” she said.

“The big challenge for our children and our grandchildren will be how to flatten this curve.”

Emissions from fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – were the main contributor to the growth in atmospheric CO2, the report said, and were responsible for about 85% of emissions from 2009 to 2018.

Rising ocean temperatures, marine heatwaves and acidifying waters were also projected to continue, posing a significant threat to Australia’s coral reefs, Brown said.

Since 1970, rainfall in the southwest of Australia had dropped by about 16% in the cooler months between April and October, but most of northern Australia had seen a rise in rainfall.

“Australian agriculture has already faced significant challenges and disruption from climate change, seen through record droughts, heatwaves and rising temperatures,” Dr Michael Battaglia, CSIRO agriculture and food research director, said.

“The effects of these are widespread, impacting food production, supply chains, regional communities and consumer prices. Our farmers are resilient and capable, but climate change exposes them to significant risks.”

Projections for Australia’s temperatures in the next two decades showed every year was warmer than it would have been “in a world without human influence”.

This, the report said, was known as “climate change emergence”.

While

the current decade was warmer than any other over the last century, the

report said it was likely to be the coolest decade of the century

ahead.

Australia would experience further warming, more extremely hot days and fewer cool days. Extreme heavy rainfall events would also increase.

There would probably be fewer tropical cyclones in the future, the report said, but those that did form would be more likely to be more intense.

Brown told Guardian Australia while the findings in the report were “confronting” it showed that “now is the time to act.”

The report’s release comes as the prime minister, Scott Morrison, faces pressure to follow major trading partners and commit Australia to a target of net zero emissions by 2050.

No comments:

Post a Comment