Extract from The Guardian

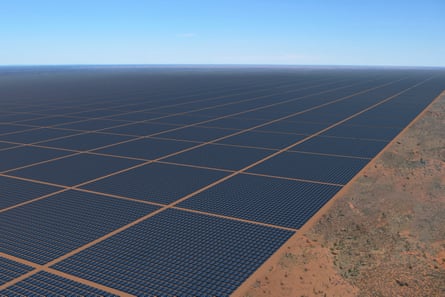

If built in full, the Asian Renewable Energy Hub will consist of 1,600 giant wind turbines and a 78 sq km array of solar panels. Photograph: Alfredo Estrella/AFP/Getty Images

The Asian Renewable Energy Hub would have an energy content equivalent to 40% of Australia’s overall electricity generation

Last modified on Sat 14 Nov 2020 06.01 AEDT

The world’s largest power station is planned for a vast piece of desert about half the size of greater suburban Sydney in Australia’s remote north-west.

Called the Asian Renewable Energy Hub, its size is difficult to conceptualise. If built in full, there will be 1,600 giant wind turbines and a 78 sq km array of solar panels a couple of hundred kilometres east of Port Hedland in the Pilbara.

This solar-wind hybrid power plant would have a capacity of 26 gigawatts, more than Australia’s entire coal power fleet. The hub’s backers say the daytime sun and nightly winds blowing in from the Indian Ocean are perfectly calibrated to provide a near constant source of emissions-free energy around the clock.

Most of it will be used to run 14GW of electrolysers that will convert desalinated seawater into “green hydrogen” – a form of energy that analysts expect to be in increasing demand as a replacement for fossil fuels in the years and decades ahead.

Though still five years away from construction, the hub vaulted closer to reality in recent weeks after the federal government granted it major project status – a designation that should smooth the approval processes – and the Western Australian government greenlit its first stage.

We have the right backing, we have the partners and it will get done.

It is an ambitious undertaking, but it is not alone. The Asian Renewable Energy Hub heads a list of projects and potential developments, many private and some government backed, that are seeking to capitalise on what the economist Ross Garnaut described as Australia’s potential to be a clean energy superpower.

While Australia’s climate politics remain stuck in gridlock, the government is focused on promoting gas-fired developments and – Covid-19 aside – national greenhouse gas emissions have largely flatlined in the years since the Coalition abolished an overarching federal climate policy. However, the plummeting cost of solar and wind energy is encouraging investments that seemed unlikely not long ago.

The pace of investment in large-scale clean energy has slowed since the 23% national renewable energy target was filled and not replaced last year, but state governments and corporates are filling some of that gap.

This week alone there were a string of extraordinary announcements. The New South Wales government plans to underwrite 12GW of renewable energy and 2GW of storage over the next decade, Woolworths is promising to run its supermarkets and operations on 100% green energy within five years, and the country’s biggest super fund, AustralianSuper, dumped its shares in Whitehaven Coal as it set a path to a net-zero emissions investment portfolio by 2050.

Perhaps most remarkably, Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest foreshadowed that his Fortescue Metals Group would move aggressively into renewable energy, setting a goal of building 235GW across the globe.

Here are some of the other green shoots and big ideas that are on the horizon or, in some cases, already with us.

Green hydrogen exports: the Asian Renewable Energy Hub

The Pilbara project was initially planned as a means to sell green energy to coal-rich Indonesia via sub-sea cable. That idea has been dropped in favour of hydrogen, based on the expectation that by 2035 the world will be looking for vast amounts of green fuel to replace coal, gas and oil.

Alex Hewitt, the founder and director of CWP Renewables, an Australian-based partner in the hub, says the $53bn development is the country’s first “renewable energy project at oil and gas scale” – and a sign of where the world is headed.

“The buzzwords here are scale and urgency,” he says. “When fully operational this will produce 1.8m tonnes of hydrogen every year for decades, with an energy content equivalent to 40% of Australia’s overall electricity generation.”

All being well, Hewitt says, its first shipment of green energy into Asia will be made in 2027.

Hydrogen has grabbed the attention of politicians and industry, including winning support at federal and state level in Australia. There are more than 20 smaller hydrogen projects under way across the country, but the hub dwarfs them. Hewitt says it will allow the fuel to be produced for less than $2 a kilogram, the level at which the Morrison government expects it to be cheaper than fossil fuel alternatives.

“It’s amazing how fast the transition is coming,” he says. “All the technology we’re using is proven at demonstration level. We have the right backing, we have the partners and it will get done.”

The consortium expects 3GW of its solar and wind capacity to be used locally to power mining sites and large trucks, replacing 3bn litres of imported diesel used in the Pilbara each year. Some of the energy may help create new industries such as green steel, which is seen as a significant economic opportunity once coal-fired processes can be affordably replaced with renewables and hydrogen.

But most of the energy created will be exported. Because hydrogen condenses from a gas into a liquid only at very low temperatures (about -250C), it will be shipped as green ammonia, which is safer to transport and created by blending hydrogen with nitrogen.

While not everyone is as bullish, the consortium believes the applications for green hydrogen and ammonia may be as broad as fossil fuels are today, including heavy road transport, long-range shipping and aviation, fertiliser production, energy-intensive big industry such as mining operations, and electricity generation. On the latter, they are closely watching a Japanese trial using ammonia to co-fire an existing coal power plant.

Solar exports: Sun Cable

The second of Australia’s two giant renewable export projects is no less extraordinary in its ambition, and also has been granted major project status from the federal government. Like the Asian Renewable Energy Hub, it is billed as the largest of its type in the world.

The $22bn Sun Cable proposal, backed by billionaires Mike Cannon-Brookes and Forrest, involves building a 10GW solar farm with battery storage at the Newcastle Waters cattle station about 750km south of Darwin.

Some of the electricity may be used to help power the Northern Territory capital and Indigenous settlements, but most would be intended for transmission via sub-sea cables that would snake 3,800kms through the Indonesian archipelago to Singapore. Sun Cable’s chief executive, David Griffin, has said the project could provide up to a fifth of the city-state’s electricity.

Long-distance high-voltage direct current submarine cables are used in Europe, but this would be the world’s longest by some distance. The NT government last month announced the project had reached the first stage of the environmental approvals process, and Sun Cable has begun discussions with authorities in both Singapore and Indonesia and surveyed the first 750km of the route.

Its goal is to start construction in late 2023 and, like the Pilbara hub, to be exporting by 2027.

Offshore wind energy: the Star of the South

While onshore wind and solar have boomed in recent years as developers rushed to fill the national renewable energy target, Australia is yet to follow other countries – particularly in northern Europe and Britain – in building turbines off the coast.

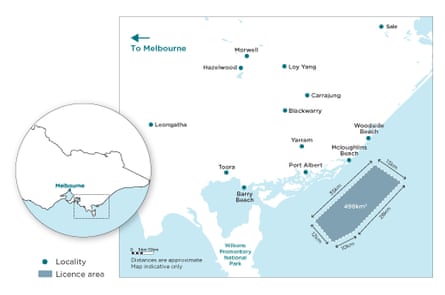

That may change with a proposal to construct a 2.2GW windfarm in Bass Strait off Port Albert and Mcloughlins Beach in South Gippsland.

According to the proponents, the $10bn project would be one of the world’s largest offshore windfarms, and likely to meet about 20% of Victoria’s electricity needs.

It would involve a yet-to-be-determined number of turbines – the company just says hundreds – of between 185 and 245 metres being built on the seabed between 7km and 25km offshore.

It is potentially a sensitive place to build, with plans needing to factor in the impact on marine life and of grid connections to the Latrobe Valley inland.

One of the questions hanging over the project will be its cost, but Star of the South maintains it makes economic sense – that the technology is becoming cheaper and the generation patterns of offshore wind will complement, rather than compete with, onshore renewables. It is seeking environmental approval from the Victorian government and waiting on the commonwealth to complete a legal framework for offshore clean energy developments, but has a goal of starting to generate by 2025.

Energy security: large-scale batteries

Where offshore wind is in its infancy, batteries are being built at a pace few expected.

Just four years ago, the Australian Energy Market Operator forecast that the country might have only 4MW of large-scale batteries by 2020, and build no more before 2036.

The reality is a marked

contrast. There is already 287MW in operation or committed to

construction, including several batteries built alongside wind or solar

developments. Last week, the Victorian government announced a contract

for a 300MW battery near Geelong – larger than everything built to date and billed as one of the biggest in the world.

While batteries are often assumed to be storing surplus energy from the middle of the day for use when the sun goes down, the primary use so far in Australia is to bolster the security of the grid. When something goes wrong — such as a major transmission line being taken out by a tornado or a power station “tripping”, as happens more than 100 times a year — batteries are called on plug the gap in a fraction of a second, preventing the grid from collapse.

Simon Holmes à Court, a senior adviser to the Climate and Energy College at Melbourne University, said they were an attractive option for state governments wanting to strengthen their grids at modest cost. Independent reviews found Australia’s first big battery, built at Hornsdale in South Australia in 2017, saved consumers $150m in its first two years in operation.

Expect to see more of them, rapidly. “Falling costs and greater familiarity of the technology have led to solar and wind developers increasingly building batteries into their plans,” Holmes à Court says.

Australia’s biggest power plant: rooftop solar

Perhaps the Asian Renewable Energy Hub will one day pass it, but for now the biggest power plant in the country is spread across 29% of Australian homes. By the middle of this year, the country had about 12GW of solar rooftop panels, with installations continuing at a pace unaffected by Covid-19 or the gradual winding back of government incentives.

Investment in large-scale renewable energy fell this year, but the growth in small-scale solar has increased to fill the gap. It is expected 2.9GW will go up this year, equivalent in capacity to a couple of average-sized coal plants. It has prompted authorities to take steps so panels can be temporarily disconnected from the grid if the influx of solar power causes problems for grid security. The 20th-century electricity system, based on a handful of large generators, was not built to cope with an influx of distributed power.

A better solution may be to make it more financially attractive to install household batteries, which if pooled together can operate as a centrally controlled virtual power plant, charging or dispatching energy to the grid as needed. South Australia is trialling this sort of system, but for now incentives are limited in most states.

In the meantime, analysts expect the skyrocketing installation rate to continue, reflecting the International Energy Agency’s observation that solar can now offer the cheapest electricity in history.

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment