Economic growth is slow, Australia’s population is ageing and the climate crisis looms. The burden of these changes mainly falls on the young

Each new generation of Australians since federation has enjoyed a

better standard of living than the one that came before it. Until now.

Today’s young Australians are in danger of falling behind.

A new Grattan Institute report, Generation Gap: Ensuring a Fair Go for Younger Australians, reveals that younger generations are not making the same economic gains as their predecessors.

Economic growth has been slow for a decade, Australia’s population is ageing, and climate change looms. The burden of these changes mainly falls on the young. The pressures have emerged partly because of economic and demographic changes, but also because of the policy choices we’ve made as a nation.

A new Grattan Institute report, Generation Gap: Ensuring a Fair Go for Younger Australians, reveals that younger generations are not making the same economic gains as their predecessors.

Economic growth has been slow for a decade, Australia’s population is ageing, and climate change looms. The burden of these changes mainly falls on the young. The pressures have emerged partly because of economic and demographic changes, but also because of the policy choices we’ve made as a nation.

Why younger generations are falling behind

For much of the past century, strong economic growth has produced growing wealth and incomes. Older Australians today have substantially greater wealth, income and expenditure compared with Australians of the same age decades earlier.But, as can be seen from the yellow lines on this graph, younger Australians have not made the same progress.

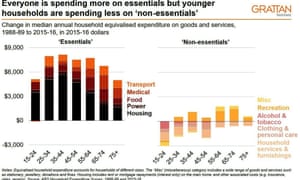

In fact, as the graph below shows, while every age group is spending more on essentials such as housing, young people are cutting back on non-essentials: among them alcohol, clothing, furnishings and recreation.

If low wage growth and fewer working hours becomes the “new normal”, we are likely to see a generation emerge into adulthood with lower incomes than the one before it.

It has already happened in the United States and United Kingdom.

Our generational bargain is at breaking point

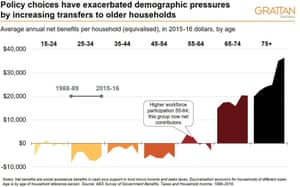

Budget pressures will exacerbate these challenges.Australia’s tax and welfare system supports an implicit generational bargain. Working-age Australians, as a group, are net contributors to the budget, helping to support older generations in their retirement.

They’ve come to expect that future generations in turn will support them.

But Australia’s population is ageing – which increases the need for government spending on health, aged care and pensions at the same time as there are relatively fewer working age people to pay for it.

Demographic bad luck is one thing (some generations will always be larger than others) but policy changes are making the burden worse.

A series of tax policy decisions over the past three decades – in particular, tax-free superannuation income in retirement, refundable franking credits, and special tax offsets for seniors – mean we now ask older Australians to pay a lot less income tax than we once did.

Disturbingly, these and other changes mean older households now pay much less tax than younger households on the same income.

The overall effect has been to make current working Australians increasingly underwrite the living standards of retirees.

As it happens, it is also more than the typical 40-year-old is contributing to his or her own retirement through compulsory super.

This can’t be what Australians want

It’s time to make sure we do it.Lots of older Australians are doing their best, individually, supporting their children via the “bank of mum and dad”, caring for grandchildren, and scrimping through retirement to leave their kids a good inheritance.

These private transfers help a lucky few, but they don’t solve the broader problem. In fact, inheritances exacerbate inequality because they largely go to the already wealthy.

We need policy changes.

Reducing or eliminating tax breaks for “comfortably off” older Australians would be a start.

Boosting economic growth and improving the structural budget position would help all Australians, especially younger Australians. It would also put Australia in a better position to tackle other challenges that are top of mind for young people, such as the climate crisis.

Changes to planning rules to encourage higher-density living in established city suburbs would help by making housing more affordable.

Just as a series of government decisions have contributed to the challenges facing young people today, a series of government decisions will be needed to help redress them.

Every generation faces its own unique challenges, but letting this generation fall behind the others is surely a legacy none of us would be proud of.

It’s time to share the burden, and perhaps an avocado latte while we’re at it.

• Kate Griffiths is a researcher at the Grattan Institute; Danielle Wood is program director, budget policy and institutional reform at the Grattan Institute

• This article was originally published in the Conversation

No comments:

Post a Comment