Though born into Hollywood royalty, the charismatic actor sidestepped

conventional leading man roles and installed himself at the epicentre

of the 60s youthquake

In cinemas, the summer of 2019 has already been a strange reprise of August 1969, thanks to Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood

delighting crowds with a what-if vision of Tinseltown history. Amid the

namedropping in the film, the lack of reference to Peter Fonda is

telling. If the whole point of it is to present a Hollywood

counterfactual, one where the hippies never took over the movie

business, then Fonda – whose role in that true story was more pivotal

than any other – is best written out altogether. It is, in fact, a

tribute.

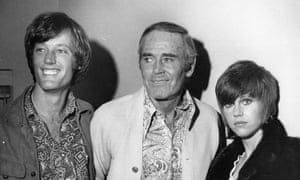

Fonda could have easily chosen to have been elsewhere. His childhood was streaked with tragedy and novelistic incident – the suicide of his mother, Frances Ford Seymour, when he was 10; the episode soon after when he accidentally shot himself in the stomach. Still, he had a golden future laid out for him, having been born into film business nobility, the son of a grand movie everyman in his father, Henry; his sister Jane a star, too, by the mid-60s. The kid of the family, leading man handsome, was surely next in line.

He was there, too, at the Sunset Strip riots in 1966, which erupted in protest at police harassment of the shaggy teenagers flocking to LA. He was not only present, but arrested. Something was simmering in America, and Fonda was key to it, off camera and on. Marginalised by Hollywood, he starred instead in the films that first gave big-screen form to the hippie moment, The Wild Angels and The Trip.

All of which meant that when Easy Rider arrived in 1969, it was propelled by real experience. Fonda was the film’s producer – the budget topped up by his credit card – as well as its star. His long-limbed, blue-eyed Wyatt was the perfect foil to Dennis Hopper’s scratty freewheeler Billy. And his life was in the soul of the movie. The power of Easy Rider wasn’t that it was a story of outlaw potheads, starring off-the-shelf hairy male leads. By 1969, anyone could have made that. It was the sense of a movie being of a generation, made without executive permission, that electrified a Vietnam-sick audience. It spooked the studios so badly they set loose untold cocksure young directors – Scorsese and Coppola et al – in a desperate attempt to play catch-up.

Few careers cause even one earthquake – and yet the sense of everything after 1969 as a postscript would be unfair. In the wake of Easy Rider, Fonda directed a pair of films – The Hired Hand and Idaho Transfer – with a loping personality well worth rediscovering. As an actor, he earned an Oscar nomination for the bittersweet Ulee’s Gold (1997). More wonderful still was The Limey, a playful crime thriller directed by Steven Soderbergh exactly 30 years after Easy Rider. The 60s were all over the film: Terence Stamp, the face of swinging London, was cast as an ageing ex-con colliding in LA with wealthy record producer Terry Valentine. Fonda was Valentine, a relic from the counterculture who never grew up and had made all manner of compromises because of it. Soderbergh included a shot of a billboard where Valentine advertised American Express; the original ad had starred Fonda – a wry and fearless note of self-deprecation.

To change history is one thing – to be frank about what happens afterwards takes rare honesty. And yet Fonda never did much compromise. He was still often on the back of a bike until near the end of his life, and in our recent troubled years, could be found assailing Trump on social media, forever an elegant rebel, happy in the now.

No comments:

Post a Comment