Extract from The Guardian

Experts say they believe the US president-elect will exert significant pressure on Australia to lift its climate commitments

Last modified on Sun 8 Nov 2020 07.30 AEDT

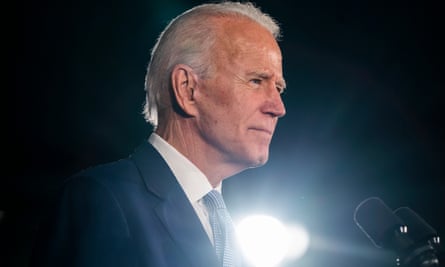

Australia risks becoming an isolated laggard in addressing the climate crisis, without obvious allies to shelter it from rising international pressure to act, as the US takes a leadership role under Joe Biden, experts say.

The president-elect has declared addressing climate change “the No 1 issue facing humanity” and promised $2tn in climate spending and policies to put the US on a path to 100% clean electricity by 2035 and net zero emissions no later than 2050.

Biden last week promised to rejoin the Paris agreement, which due to a quirk of timing the US officially left on the day after the election, on his first day in office and has said he would “use every tool of American foreign policy to push the rest of the world” to increase their ambition to combat the problem.

With the Democrats in the White House, every member of the G7 and the European Union will be committed to net zero emissions by 2050. China – comfortably the world’s biggest annual emitter – says it will be carbon neutral before 2060. The Morrison government has resisted setting a specific long-term emissions goal, saying it would reach net zero “in the second half of the century”.

Howard Bamsey, Australia’s former special envoy on climate change, said Biden’s win demonstrated “even more clearly that the world is indeed changing” in its response to the issue. Japan and South Korea – the world’s fifth and seventh-biggest emitters respectively and, with China, the biggest markets for Australia’s fossil fuel exports – last week set carbon neutrality targets for 2050.

Bamsey said Biden’s election would likely affect climate action in two ways – by increasing the confidence of major investors to back clean solutions as it became even clearer the world was moving away from fossil fuels, and by “radically” transforming climate change diplomacy ahead of the major international conference in Glasgow in November 2021.

He said the Morrison government risked being left with no obvious allies on the issue if it continued to stand apart from increasing action and co-operation.

“There’s no cover any longer with this,” Bamsey said. “I think in Joe Biden’s first conversation with Scott Morrison, or the second, climate change will be mentioned. It’s been such an important part of his campaign and he clearly recognises the economic imperative for change.”

Dean Bialek, a former Australian diplomat to the UN now working with the British government in preparing for the Glasgow conference, said much of the world was increasingly seeing climate action as an economic opportunity, rather than a burden.

He said Australia had faced significant pressure to lift its climate commitments at the UN climate conference in Madrid last year, and risked being further isolated as a climate laggard alongside only Brazil, Russia and Saudi Arabia among G20 countries if it stuck to its current position.

“It means that the shadows that Australia has been hiding in are much smaller now, particularly with China, Korea and Japan having moved on net zero in recent weeks,” Bialek said. “It starts to smell like a government that doesn’t care about climate change.”

With most major economies now promising net zero emissions by mid-century, it is expected attention in climate diplomacy will turn to countries increasing their commitments to act over the next decade, a period scientists have advised is crucial if countries are to live up to the commitment under the Paris agreement to “pursue efforts” to limit global heating to 1.5C.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimated hitting that mark would require about a 45% cut in global emissions below 2010 levels by 2030. With global action falling far short of that – global emissions rose slightly last year – scientists say the globe is on track for more than 3C of heating, a change they say would have far-reaching and catastrophic consequences.

The Morrison government has a 2030 emissions target of a 26%-28% cut below 2005 levels, having rejected a science-based recommendation by the Climate Change Authority of a reduction of between 45% and 60% over that timeframe. Prior to Covid-19, national emissions had reduced just 2.2% since the Coalition was elected in 2013 and official data released last December suggested Australia would miss its 2030 target unless it used a contentious carbon accounting measure rejected by other countries.

The Coalition has backed a “technology, not taxes” approach to climate change, setting “stretch goals” to reduce the cost of five low-emissions technologies to make them competitive, but the goals are not tied to a timeframe or an emissions reduction trajectory.

Frank Jotzo, director of the Centre for Climate Economics and Policy at the Australian National University, said Biden would be expected to announce a stronger 2030 target (the US’s current short-term goal is a 26%-28% cut by 2025) before the Glasgow summit, as expected under the Paris agreement.

While the Democrats appear only an outside chance to control the Senate – likely to be necessary if it is to pass significant national climate legislation – Jotzo said a Biden administration would be expected to re-strengthen institutions and bring back climate friendly regulations abolished under Donald Trump. A taskforce led by former secretary of state John Kerry and congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez identified 56 policy steps on climate and energy that would not need Congress support.

Jotzo said he expected the US to exert significant pressure on Australia “to stop being a recalcitrant on this issue”.

“They will find some common ground, maybe a lot, on the tech development side of things,” he said. “But the US will say this is not enough, not nearly enough, and that Australia also needs to move ahead and deploy low-carbon technology and transition from a fossil fuel based economy to a renewables based economy.”

Speaking on the ABC on Saturday, moderate Liberal backbencher Trent Zimmerman said one of the pluses of a Biden presidency would be a re-engagement and increased focus on climate change.

“I actually see opportunities for Australia in that,” he said. “We have said, as Joe Biden has said, that we want to develop a technology roadmap to ensure that we are playing our role in emissions reduction, and I actually see the opportunity for us to be working with the United States on many of those areas.”

He said the government had similar arrangements with Germany and Korea on clean hydrogen. “I think that the closeness of our relationship with the United States means there will be considerable and new economic opportunities as we explore some of the natural strengths that Australia has in areas like renewable energy,” Zimmerman said.

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment