Extract from The Guardian

The six-year round trip to an asteroid named Ryugu will end in the red sands of Woomera, Australia

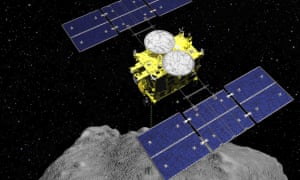

The Japanese space agency’s remarkable Hayabusa2 mission will on Sunday deliver the second-ever artificially collected sample of asteroid material when a return capsule falls to Earth at the Woomera rocket range in South Australia.

The Hayabusa2 probe has been on a 6bn km, ¥30bn ($388m) round trip to an asteroid named Ryugu, which started six years ago in December 2014. After landing on Ryugu twice last year, the spacecraft began its return journey to drop a capsule protected by a heat shield to deliver its payload.

While the capsule is whisked away to have its precious contents analysed, the vehicle that brought it will keep sailing into space – to rendezvous with asteroid 1998 KY26 in 2031.

Back on asteroid Ryugu, the mission has left a new archaeological site sprawled across the surface consisting of four rovers, three craters, a camera, an impactor, and four reflective markers. These are 10cm, silvery, sub-spherical balls printed with a grid pattern that serve as wayfinding beacons in an unknown land.

In 2018, the rovers Hibou, Owl and Mascot landed on the surface of Ryugu. Armed with cameras and other instruments, their task was to survey the terrain of the 1km asteroid.

We’re used to planetary rovers with sturdy wheels trundling along slowly, like Curiosity on Mars and Yutu 2 on the Moon, but Hayabusa’s rovers used a unique mechanism to jump across the surface like little solar-panelled spiders. Their 16 stumpy legs probably punctured the surface with each hop.

A fourth rover, Minerva II-2, didn’t wake up after hibernation on the way to Ryugu. It was used to make gravitational measurements and then crashed into the surface.

These artefacts tell the story of a very busy period of engagement with the asteroid over 2018-2019, when it was measured, filmed, prodded and poked, finishing with a “biopsy” when the parent Hayabusa2 craft shot a device under Ryugu’s weather-beaten skin and removed 1g of material. This may not seem like a lot, but it’s riches compared to the mere 1,500 grains of dust that the precursor mission Hayabusa 1 sent back from asteroid Itokawa in 2010.

Now Ryugu is still and silent again – the rovers have run out of power and stopped hopping. There’s no longer even the shadow of the Hayabusa2 craft as it circles the tiny asteroid. Nothing moves on the surface.

The asteroid isn’t a blank rock any more, though: the mission enabled us to name places in the landscape of this mini-world. Ryugu itself is the name of a mythical underwater palace in Japanese folklore. Fairytales provided the theme for 13 craters and other features. Unofficially, Mascot’s landing spot became known as Alice’s Wonderland.

There’s a surprising number of human traces scattered across these small solar system bodies.

Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko hosts the remains of the European Space Agency’s Rosetta and Philae spacecraft. The Near Shoemaker probe landed on asteroid 433 Eros in 2001 after a year of making observations from orbit. Nasa’s Dawn is orbiting the dwarf planet Ceres, out beyond Mars in the main asteroid belt. Hayabusa 1 left touchdown marks on Itokawa as well as a target marker; but lost its Minerva lander, which is now orbiting the Sun. On asteroid Bennu, there’s a little smoothed depression like a dune blow-out where Osiris Rex approached to capture particles. We won’t get this sample back until 2023.

In the meantime, Hayabusa2 is about to open another window into the early history of the solar system and the big question: how life originated.

Did life evolve on Earth from the primordial slime, or was it delivered on the natural spaceships we know as comets, asteroids and meteorites?

It’s easy to think of the rest of the solar system as sterile compared to the vibrancy of Earth with its blue oceans and virulent greenery, but every new mission beyond our terrarium in the last decade has shown that water is far more abundant than we thought.

And where there is water, there is the potential for life, particularly if we also find complex “prebiotic” molecules. Jaxa targeted Ryugu because it is rich in such carbonaceous compounds and can tell us something about their distribution.

Planetary Protection guidelines set conditions on missions to places where there might be life to avoid contaminating or killing potential neighbours hiding in subterranean or subglacial oceans.

Perhaps we shouldn’t see ourselves as separate from this process, but part of it.

“Panspermia” is the theory that life is everywhere. Future space archaeologists or astrobiologists may look at discarded human artefacts in the solar system as interplanetary travellers distributing terrestrial materials, both living and non-living, in the same way as meteorites.

Humans might be the agents of non-human life colonising ecological niches on other worlds, our own grand plans of multiplanetary occupation abandoned as our flimsy bodies prove far less adaptable than those more seasoned space travellers, the microbes.

When the Hayabusa2 return capsule hits the red sands of Woomera to be eagerly greeted by the teams of waiting scientists we’ll have another tiny piece in the puzzle of life, the universe and everything.

No comments:

Post a Comment